By Tim Daugird

What if I told you that if enough people got a flu shot, we could all eliminate influenza outbreaks? You may think, “Duh, if everyone got a flu shot, then no one would get the flu”. Although you would be correct, we can probably all agree that the idea of everyone getting a flu shot seems a little unrealistic. What if I was a little more specific and told you we could substantially reduce flu outbreaks by immunizing less than half of the population? It may seem like a trick, but this is actually true and it is due to what scientists call herd immunity.

When you get a flu shot, you are effectively introducing your immune system to what the flu looks like. This way, your immune system knows what to look for. If it sees the flu virus again, it can destroy it right away before you get sick. This means that you are essentially protected from getting the flu. This is all fine and good, but it doesn’t explain how immunizing less than half the population can stop outbreaks. The reason that herd immunity works is because of the simple fact that if you can’t get the flu, you can’t give the flu to anyone else.

Still not convinced? It’s actually a little simpler than you might think.

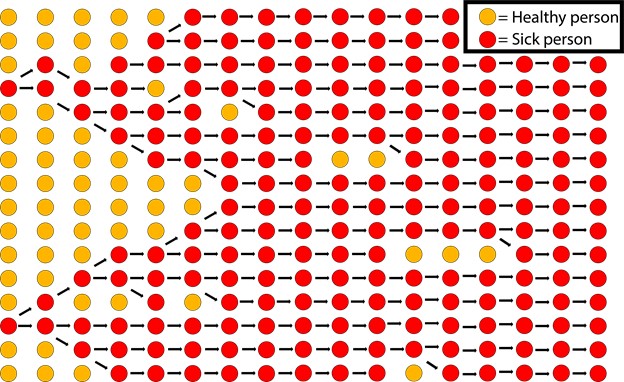

Before we look at the effects that vaccines can have on stopping outbreaks, let’s try to get an idea about what a how a virus could spread through a population where no one gets vaccinated. Below, I diagrammed a hypothetical influenza outbreak if no gets a flu shot. Each dot represents one person. I have made it so that most people that get sick will infect one additional person, with some people infecting two additional people and some people infecting no additional people. Exact estimates vary, but this is in agreement with about how contagious the actual influenza virus is.

Yikes! This is a pretty dreadful result. Starting on the left with just two sick people, it doesn’t take long for the flu to spread through a population and get almost everyone sick.

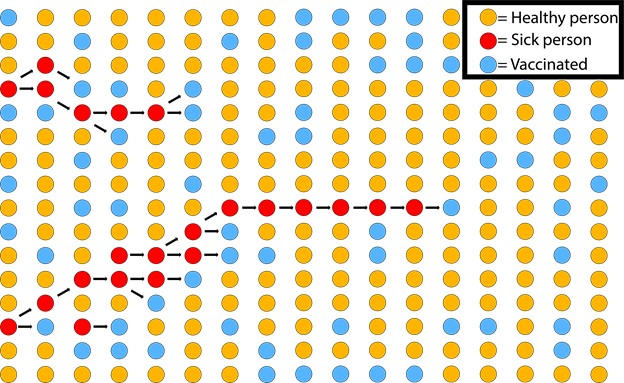

Now, if we take the exact same starting points, make all of the same assumptions about who infects who, but we randomly give 30% of the population a vaccine:

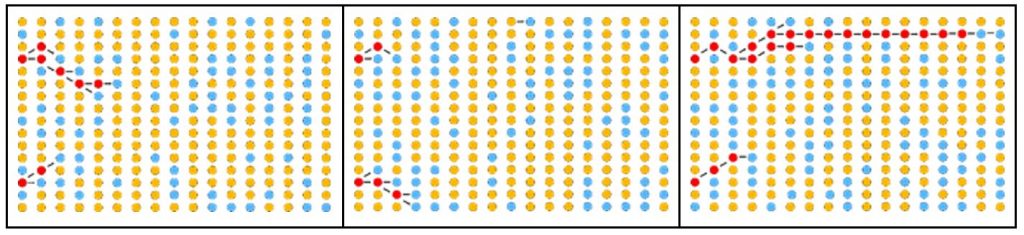

This is a much better result. Maybe we just got lucky. To convince you this isn’t about luck, I did it three more times, changing only who gets a flu shot:

I could repeat this multiple times over and although the details would change, the end result would be that a lot fewer people get sick.

These are, of course, not exact replicas of how the flu spreads. The flu shot isn’t 100% effective, and populations are considerably more complicated than these pictures. However, these pictures do convey the basic idea how getting a flu shot protects not only you from getting the flu but can help protect an entire community from an uncontrollable outbreak.

I have talked about herd immunity in the context of the flu, but this idea translates to all infectious diseases for which there is an effective vaccine. If you need more convincing, there is some pretty simple math that give a little more insight into how herd immunity works. Perhaps most convincing though is that there is a wealth of historical results of vaccination programs against infectious diseases such as measles and polio that show just how effective vaccines can be.

So next flu season, remember, getting a flu shot doesn’t just help keep you from getting sick, it can help keep us all from getting sick.

Edited by Christian Agosto-Burgos and Elise Hickman