By Alan Curtis

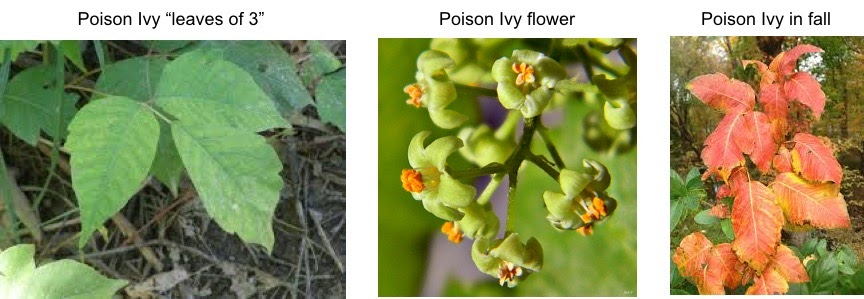

Hiking can be a fun and rewarding form of exercise but it comes with plenty of dangers ranging from blistered feet to wild animals. One of the most common dangers, however, is a seemingly harmless plant called Toxicodendron radicans, or more commonly, poison ivy. Poison ivy is a hardy, flowering summer plant found throughout the Eastern United States and in parts of China. It flowers from early May through July.

Humans often recite the old campfire rhyme “leaves of three, let them be” to help identify and stay away from the plant, as most people are allergic to a particular oil in the sap. Exposure to the oil causes a nasty, itchy, oozy red and often quite painful rash. Some believe the plants produce this oil as a purposeful defense mechanism used to ward off predators, but this is inaccurate. The oil (urushiol) actually protects the plant from dehydration (and is part of the reason it grows so well in many different climates). Urushiol is not harmful to most species. Poison ivy flowers provide nectar for bees and the leaves are a food source for deer, bears, and other mammals. So why must humans (also a mammal) avoid it while other animals use it as a snack?

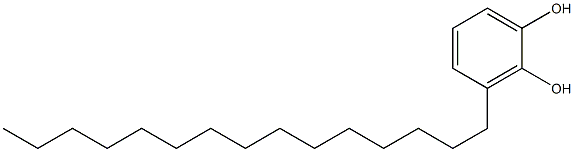

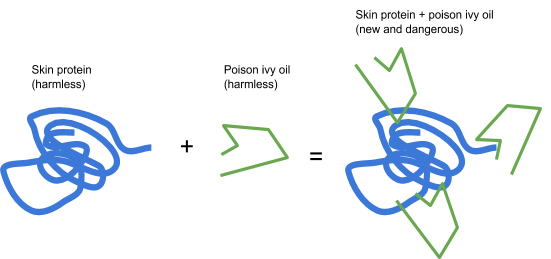

Urushiol is an incredibly sticky oil made of a variety of similar molecules, the most common of which is pentadecacatechol (seen above). It’s harmless by itself, but when it reacts with proteins in skin, it can generate an immune response. Immunologists call these types of substances haptens.

Immunology (the study of our body’s defense system) can tell us a lot about the rash caused by poison ivy. Poison ivy rash is caused by delayed type hypersensitivity, a process where special immune cells called T-cells generate an allergic response. This is different from other types of allergy (like pollen or food allergies) that are caused by other immune cells, primarily B-cells.

If the oil is washed off within an hour or so, there’s no need to worry. However, if the oil is not removed quickly, proteins on the surface of skin cells will react with it. When this happens, the harmless oil changes the shape of skin proteins to make a new antigen (a substance the immune system can interact with). This new antigen is then “presented” to the T-cells for inspection. Since this antigen is strange and new, the T-cells will launch an attack.

T-cells in the skin kick into high gear and try to defeat the new antigen. T-cells will multiply themselves first and this takes time. In some cases a person might not even start to itch for a full two days! This is why it is called delayed type hypersensitivity. Once the T-cells have an army built up, they are relentless! They call in another immune cell type, called macrophages, that release massive amounts of inflammatory proteins into the area. These proteins lead to swelling, itch, redness, and tissue damage. A doctor would identify this rash as contact dermatitis.

In most cases, contact dermatitis can be treated easily at home. The first step is to wash the skin really well with soap and water to remove the oil. Remember, the oil is quite sticky and can be spread around by scratching and toweling so make sure to clean everything (even the towels) really well. Once the oil is removed, skin cells will slowly return to normal and the immune response causing the rash will fade away. With the immune response over, healing can begin.

Specific remedies for the rash include cortisone cream or calamine lotion. Cortisone is a steroid that works to reduce itchiness, redness, and scaling by putting the brakes on the immune response. Calamine lotion calms itch and helps dry out the ooziness that can sometimes accompany the rash. In some severe cases, a physician may prescribe steroid pills to reduce the reaction. This is often needed if the oil is swallowed or inhaled (you can be exposed to the oil from a neighbor burning leaves). Sometimes, intense scratching can result in bacterial or fungal infection that will require treatment by a doctor as well. But remember, the little rhyme “leaves of three, let it be” can help you prevent it altogether! Enjoy the outdoors (with social distancing) and be safe this summer!

Edited by Rami Major and Anna Wheless