By Gabrielle Quickstad

Have you ever walked down the aisle of your local department store and taken a look at the labels on food containers or water bottles? Often, you’ll see a label proclaiming that the product is “BPA-free”. So what is BPA, and what does “BPA-free” really mean?

BPA, or bisphenol A, is a chemical building block used to make epoxy resin, known for its strong adhesive properties, and polycarbonate plastic, a naturally transparent thermosoftening plastic. Interestingly, BPA is also known as a xenoestrogen because it can mimic estrogen, a hormone important in both reproductive and sexual development. BPA is used to make a variety of common consumer goods. These include smartphones, water supply pipes, dental sealants, food packaging, baby bottles, and adhesives. The list of products containing BPA is a lengthy one; in fact, most of us interact with this chemical on a daily basis.

BPA was first created by Russian chemists in 1891, but its production didn’t really increase until the 1950s with the advent of the plastic industry. However, it wasn’t until the 1990s that BPA was identified as a potential health concern. Researchers studying estrogen activity observed an estrogen-like molecule growing in experimental flasks containing yeast. Eventually, they realized that the molecule they observed was actually leaking out of the plastic container flasks and it was none other than BPA. Since then, there have been countless studies on BPA and its potential health risks. This has led to a growing public outcry for BPA-free products, which come with their own caveats. So what are the actual effects of BPA, and why should we care if it’s in our soda cans and smartphones?

One study looked at BPA exposure worldwide and found actual exposure levels to be “hundreds to thousands of times below the safe intake limit.” On the other hand, some studies claim that BPA has a significant effect on human health. In a study looking at BPA and its potential link to heart disease, researchers found that adults with the highest amount of BPA detected in their urine were twice as likely to suffer from heart disease. In fact, over 90% of the U.S. population has BPA present in their systems, making it a priority to determine its effects on the human body.

Currently, multiple branches of the U.S. government, including the FDA and the National Toxicology Program are working collaboratively on the CLARITY Study to determine any long-term health effects caused by BPA. So far, their results indicate that “there is no risk of health effects from BPA at typical human exposure levels.”

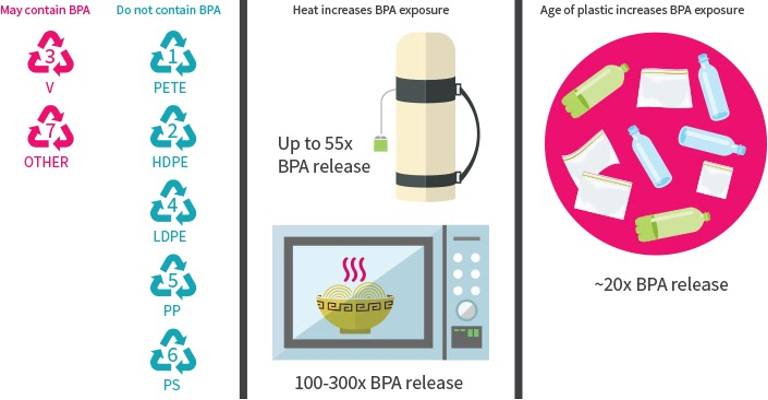

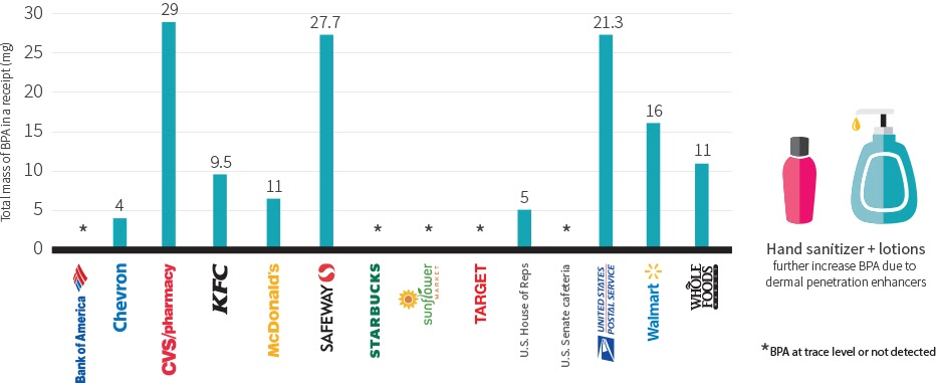

It’s worth noting, however, that there are still products containing BPA that present causes for concern. For example, thermal paper used to make receipts contain a massive amount of free BPA that can be easily absorbed by the body. One receipt has about 60 to 100 milligrams of free BPA, which is a million times more than what is found in a water bottle. Even more concerning, over 1 million pounds of BPA are released into the environment each year. This suggests that coming into contact with BPA is easy, if not unavoidable, for wildlife, including sensitive aquatic organisms. In research studies, when laboratory animals were exposed to similar levels of BPA as would be seen in the environment, they showed effects that researchers identified as a potential cause for concern.

As consumers, it’s important that we understand what it means to have BPA present in our products. Many companies are switching out BPA for other chemicals in order to list their products as “BPA-free,” either as a marketing tactic or simply to comply with new state laws (e.g. California). One of these alternative chemicals is bisphenol S, or BPS. While a study in January of this year found that both BPA and BPS had negative effects on heart function, however, BPS had a much quicker effect on the heart compared to BPA. In other words, “BPA-free products may not contain BPA, but that doesn’t necessarily make them safe.”

So is BPA actually safe for us and for the environment? Decades later, the issue is still up for debate. Regardless of the results, it’s up to us as consumers to make conscious and informed decisions about what we buy and what we release into the environment.