By Regina Fernandez

Imagine you just finished eating some delicious Bojangles’ famous chicken ‘n biscuits. Your friend sits next to you and offers a big piece of chocolate cake with two scoops of vanilla ice cream for dessert. Dessert looks delicious!! But you feel full and you don’t feel like eating anymore food. So, you decide not to eat the cake.

What causes you to stop eating once you are full? There are many factors that influence your appetite. One of them is leptin.

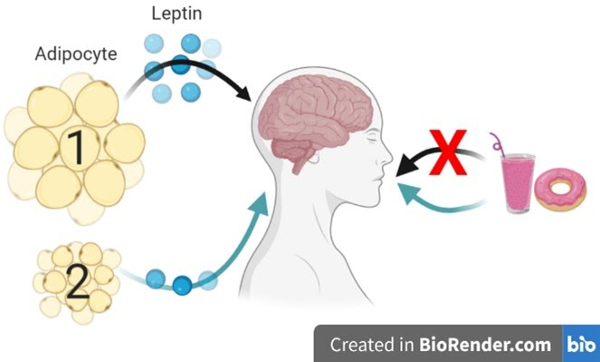

Leptin is also known as the satiety or starvation hormone and is produced mainly by adipocytes. Adipocytes are fat cells that store the energy from the food you eat as fat. After a big meal, adipocytes release leptin into the bloodstream, which travels to the brain and sends signals to a brain region called the hypothalamus. These signals result in the suppression of appetite and will prevent you from overeating. When you do not eat food for a long period of time, your adipocytes will decrease the production of leptin, and as a result your appetite will increase. The amount of leptin released by adipocytes depends on the amount of fat being stored by these cells. Thus, leptin is a hormone that plays an important role in controlling food intake.

How and when was leptin discovered?

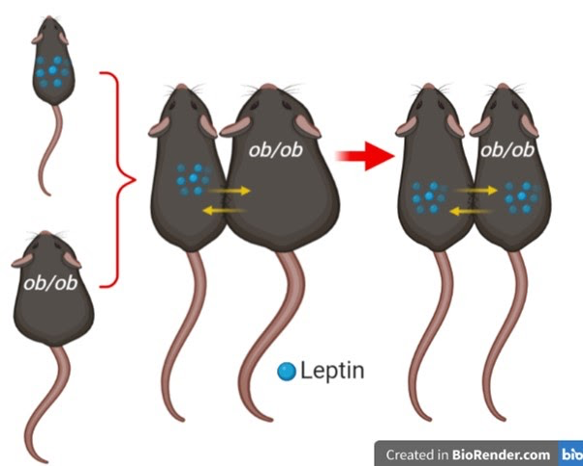

In 1949, the Nobel laureate Dr. George Snell and scientists at The Jackson Laboratories identified a group of mice that were severely obese and ate an excessive amount of food. These mice weighed up to 4 times more than a normal mouse. The scientists determined that the obesity in these mice was because of a mutation present in both alleles of the “ob” gene, which is related to obesity and thus, called the new group of mice “ob/ob”. However, the scientists were not sure what the function of the ob gene was.

In 1969, another scientist, Dr. Douglas Coleman, hypothesized that the ob gene may be producing a molecule that circulates in the blood and controls body weight and food intake in the mice. He designed a series of experiments to test his hypothesis and used a technique called parabiosis. This technique involved surgically connecting two organisms, in this case two mice, so that they exchange blood. In one of the experiments, Dr. Coleman connected a normal mouse (not expressing the ob/ob mutation) with an ob/ob mouse. The results were surprising! The ob/ob mice started to lose weight and eat like a normal mouse! The scientists concluded that the normal mouse produced a molecule that the ob/ob mice did not, and since the two mice were sharing each other’s blood, the molecule traveled through the circulation and controlled food intake and body weight of both mice.

In 1994, Dr. Jeffrey Friedman discovered that the ob gene produced a hormone. The hormone was called ‘leptin’ from the Greek word “leptos” which means “thin.” This name was chosen because leptin prevented an organism from becoming obese. Dr. Friedman also discovered that leptin is produced mainly by adipocytes, and that the levels of leptin depended on the amount of fat in the body.

In humans, a rare mutation in the ob gene causes a condition called congenital leptin deficiency, which results in extreme childhood obesity. This condition can be treated by injecting leptin. Some people have another condition called “leptin resistance”. These individuals have high levels of leptin circulating in the blood, but their brains do not respond to it, so they overeat. How leptin resistance occurs is still not well understood. However, as Dr. Friedman said, one thing is clear: obesity is a complicated disease. It is more than lacking willpower to exercise or stop eating. Many factors, including leptin resistance, can contribute to the development of obesity.

References:

- Link to Dr. Friedman’s interview: https://www.ibiology.org/human-disease/leptin/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537038/

- Coleman, D. L., Obese and diabetes: two mutant genes causing diabetes-obesity syndromes in mice. Diabetologia 1978, 14 (3), 141-8.

- Ingalls, A. M.; Dickie, M. M.; Snell, G. D., Obese, a new mutation in the house mouse. J Hered 1950, 41 (12), 317-8.

- Zhang, Y.; Proenca, R.; Maffei, M.; Barone, M.; Leopold, L.; Friedman, J. M., Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature 1994, 372 (6505), 425-32