by Taylor Tibbs

What if there was a fruit that made everything you ate taste amazing? A magical fruit that could make lemons taste like lemonade and vinegar taste like sugar syrup. As it turns out, this isn’t just mere fantasy. This proclaimed miraculous fruit does exist and it’s name is the miracle berry.

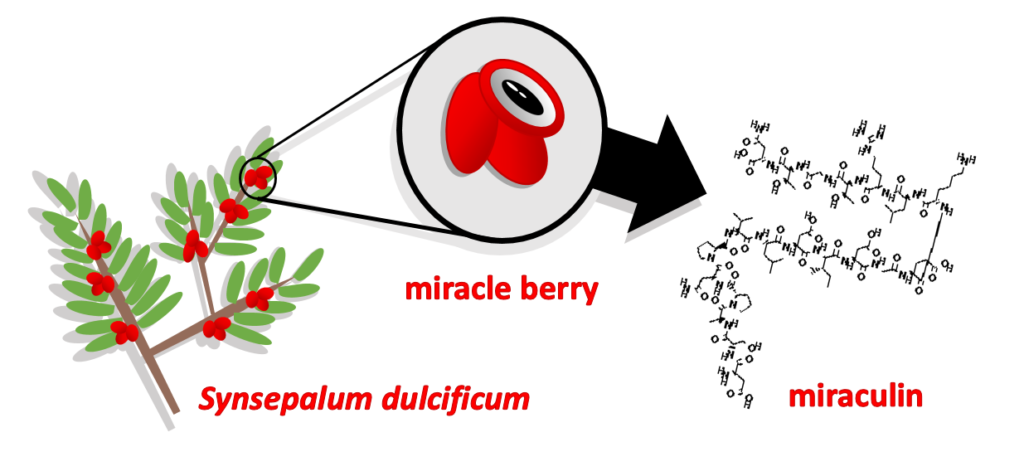

The miracle berry’s more professional name is Synsepalum dulcificum and it is a South African native. It is a green bushy plant that sports bright red, cherry tomato-like berries. Interestingly, the berries themselves are quite unremarkable in flavor. The berries really shine when combined with other foods, because they have the magic ability to turn sour and savory tastes robustly sweet. The magic, or rather the science, behind this enchanting transformation is a protein called miraculin. Miraculin strongly binds sweet taste receptors on the tongue (hT1R2–hT1R3, in humans), but only while in the presence of acid. Acid is what predominantly gives foods their sour taste. In the presence of miraculin, highly acidic fruits like lemons and limes become as sweet as hard candy and lip-puckering vinegar becomes as pleasant as maple syrup.

The miracle berry was first documented in 1756 by the French explorer Chevalier des Marchais while he was visiting Africa. African natives would chew on or mix the berry with bland or less savory foods to make them more palatable and enhance their flavor. It wasn’t until nearly 200 years later that the miracle berry gained its notoriety in the Western world when the signature protein, miraculin, was extracted in 1968.

Miraculin has since been used both commercially as an entertaining (and educational) recreational activity and as a therapeutic for individuals suffering from low appetite or loss of taste, like patients undergoing chemotherapy. Another potential therapeutic application of miraculin is to help those who need to lessen the amount of sugar in their diets, such as patients with diabetes or those struggling to lose weight. Miraculin can help sweeten bland, healthier foods that may be staples of a medically tailored diet.

Unfortunately, miraculin as a widespread sugar substitute is unlikely anytime soon (at least in the United States). The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labeled miraculin as an additive in the 1970s, after the initial attempt of commercializing the non-caloric sweetener by a company called Miralin. Additives require years of additional testing before being approved for commercial use, which at the time was a herculean task for the small company during the economic stresses of the early 1970s. Another potential strike against miraculin is that it has historically proven to be a costly crop to produce on a large scale, since the plant is not as hardy as other staple crops like corn or wheat. That being said, there have been efforts to improve the hardiness of the plant over the past 10 years by breeding them with tomato and lettuce plants.

While it may be unlikely we’ll see a low-calorie, miraculin-enhanced soda on the shelves of our local supermarket anytime soon, we can still indulge in the magic and novelty of the world’s most miraculous fruit.