By Brianna Almeida

Dr. Luciana Bachega is a postdoctoral associate (postdoc) from Brazil in the Hawkes lab at North Carolina State University (NC State) in Raleigh, NC. She received her bachelors in Biology from São Paulo State University, her masters from The Center of Nuclear Energy in Agriculture at University of São Paulo, and her doctorate in Environmental Science from Federal University of São Carlos. She studies biogeochemical cycles in soils. [Authors Note: Biogeochemical cycles are the movement of chemical elements between different parts of the Earth’s systems, for example, the water cycle, carbon cycle, and nitrogen cycle.]

Where are you from and could you explain your scientific journey to becoming a postdoc?

My hometown of São Carlos, Brazil is very similar to Raleigh in that it’s a university town. Since I grew up in this prestigious environment I knew I wanted to be smart. So, since high school I knew I wanted to go to college for biology. I liked biology and I was curious to learn about cells and DNA. So when I did my undergraduate I thought I was going to be a molecular biologist. [Authors Note: Molecular biology involves investigating the roles of proteins and nucleic acids in living organisms.] But I think it was between finishing undergrad and thinking about going to do a masters that I switched over to studying the environment.

When I started undergrad (around 2005) DNA and biotechnology was the big thing that everyone was interested in. No one was talking about environmental change. I started my masters in 2008 and that‘s when people were talking about climate change. So I changed from molecular biology to environmental science, and it was a new world but my masters was a lot of work and I decided I needed a break. I couldn’t go on to a PhD right away. So I went and taught kids for one year as a part-time research assistant in a biogeochemistry lab. My time as a research assistant further solidified my love for working in the lab. So after working in that lab for two and a half years I applied to do my PhD.

I loooooved my PhD work. I felt this was me. I never wanted to finish. If it was up to me I would have been there forever but things are not like that. So when I finished my PhD I started looking for a postdoc to get more training. My first postdoc was working in the Amazon at the National Institute of Amazonian Research. I studied the effects of CO2 fertilization on belowground biogeochemistry and nutrient processes. It was a huge experiment across an entire forest, but I was not comfortable living in that environment. So, I began looking for another postdoc position. I always had the goal of being an international researcher and did not want to conduct research in a developing country because it’s very different. So, I looked for positions outside Brazil and I found my current position at NC State. When I saw the job posting it sounded just like me and my experiences. I debated about moving to the States because I always saw myself living in Europe, but I got the position and came here.

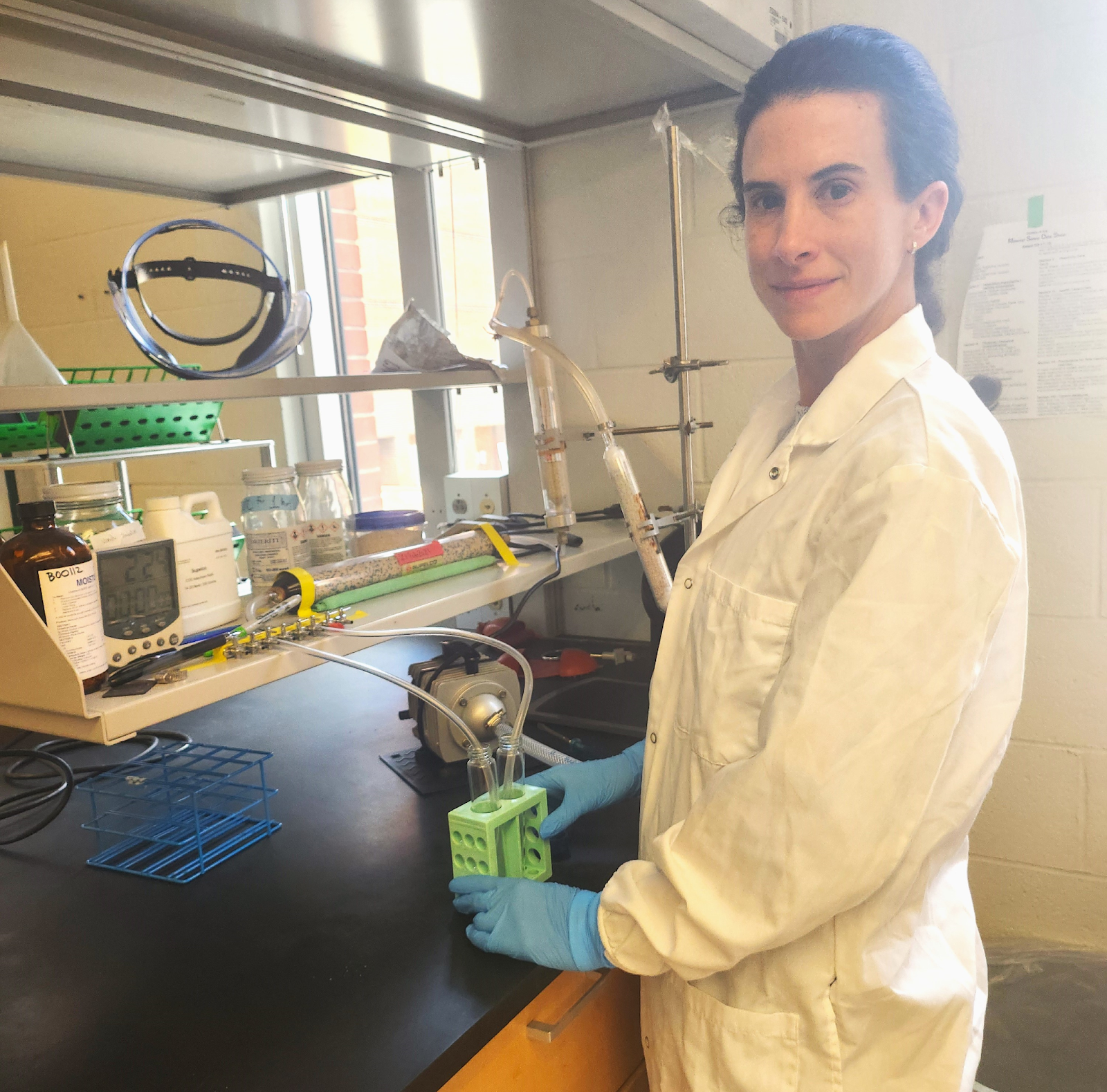

Luciana working at the laboratory bench. Image taken by Brianna Almeida.

Do you have to do a masters to do a PhD in Brazil?

Yes, you have to complete a masters. You can apply for a PhD but you need a resume as if you have the experiences from completing a masters. So doing a masters in Brazil is two years and a PhD is usually four years.

When did you know you wanted to do science?

I always thought it was very cool to be in a lab, mixing chemicals and I enjoyed getting results to answer my questions.

What is your current research focus?

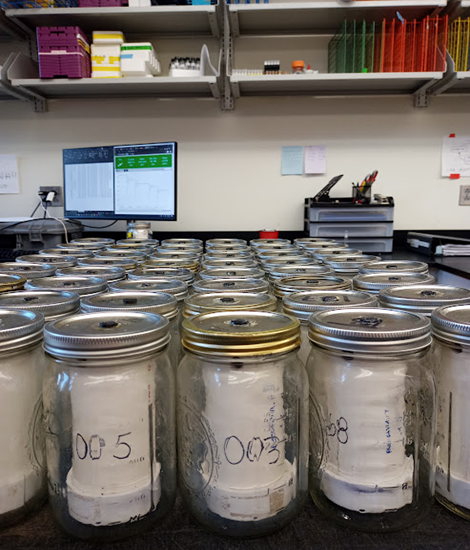

In the big picture, I research change in the environment. In my PhD I studied land use change. For example if you have land that historically had crops on it but now you want to restore that land to a more natural state, how do the biogeochemical cycles change? In my first postdoc I studied climate change and the effect of carbon dioxide on belowground processes. And now I study biogeochemical cycles under drought, more specifically under rain exclusion. This study is part of a global network of many labs conducting similar experiments around the word but always with rain exclusion. As part of this, scientists send their soils to me from their treatments under rain exclusion, which represents extreme drought, as well as their controls under normal precipitation. What we want to know is if and how extreme drought changes the microbial functions and carbon and nitrogen cycling in the soil. The experiment has gone on for five years. We’re investigating if five years of drought can change the evolution of the microbial community. The thinking is that the microbial community changes so fast but our hypothesis is that they are resilient and predict that all the communities under drought would change the same magnitude. Our collaborators at the University of Michigan are conducting experiments to assess the changes in these microbial communities.

PVC soil cores collected from all over the world. Image provided by Luciana Bachega.

What I focus on is carbon dioxide and heterotrophic soil respiration (carbon dioxide is released from soil when microbes break down organic soil matter) . I try to figure out what explains how much carbon dioxide is emitted from the soil, whether its microbial biomass, the amount of carbon, or the amount of nitrogen, etc. I also build soil moisture response curves because soil responds to moisture non-linearly. We want to be able to determine how microbes are able to access the soil moisture. [Authors Note: Soil moisture response curves are used to determine the amount of water a soil can physically hold. This is unique to each soil type and important for determining processes such as plant water uptake.]

Do you find any differences between doing science in the United States vs in Brazil?

Yes, there are lots of differences. Here (in the States), science is very pretty and state of the art and by the book. In Brazil, because of limits on funding and the availability of different equipment you have to be like MacGyver. You have to be inventing ways to get the same job done as other scientists without all the usual equipment.

There is also a big difference in costs of supplies between the states and Brazil. Here a bottle of compressed carbon dioxide is like $500 but over there is about 2000 Reals (about 5x the price of the States). In Brazil it also takes a long time to get some supplies so you have to be always planning like 3 months ahead, though it is dependent on the city you’re in. Because of this, you don’t know if you have the money to do all the experiments you want to do so we always have in our minds: “We will do what we can”. In the states more things are available so here it feels like what’s on people’s minds is always, “What’s next?”

Culturally, a difference not just in Brazil but I think in developing countries overall is that you rarely apply what you learn in your PhD. We don’t produce a lot of biotechnology, so when people get a PhD it’s usually to pursue a career in academia.

What do you enjoy about your research?

I like all the equipment I get to use during my research. I like pipettes. I like how for every question there is a protocol or specific method. In my work we often use colorimetric tests which test concentration of different chemicals based on how a solution changes color. Those are fun.

What do you do for fun?

I like doing outdoor activities like hiking. I also like traveling but recently I’ve enjoyed doing some home maintenance like painting walls and mowing the lawn.

Do you have any plans for after your postdoc?

I think people at my age are already associate or assistant professors, so some might see me as “behind” in those kinds of milestones. I’ve enjoyed being a postdoc but I think I need a new experience outside of academia so I might look into industry jobs.

What advice would you give others who want to go into research?

I think if possible you should do a PhD in the United States. When you do research here you have a lot of career options. After grad school you don’t necessarily have to be in academia forever. Here (in the States) you have an open book and can apply to different types of jobs.