by Anna Goddard

How do you know what you read on the internet is true? When learning about a new topic, writing a paper, or providing proof for an argument, having credible sources is a necessity. One such source is peer reviewed research papers. Peer review is a process where scientists evaluate each other’s work before it gets published. They assess the validity, quality, and even the originality of articles submitted for publication. The “peers” involved in the review process are other experts in the field. For example, for a paper about breast cancer, another breast cancer researcher may be a reviewer.

Peer review is the foundation of upholding scientific integrity and quality of research. It serves important roles in preventing errors, avoiding bias, promoting transparency, and maintaining public trust in science. This process aims to minimize the chance of flawed or misleading results being published, reassuring the public that research findings are based on sound science.

The peer review process also serves to avoid bias. It uses independent reviewers who are less likely to be influenced by personal or institutional biases, leading to fair evaluations. The reviewers are often anonymous, selected by the journal that the article was submitted to. The reviewers may not have any personal or professional ties to the authors of the article – for example, they do not collaborate on ongoing research. Having multiple experts weigh in keeps research objective and unbiased, ensuring that the claims made in the paper are reasonable and logical. Peer reviewers are trained to detect issues such as manipulated data, plagiarism, or overhyped claims.

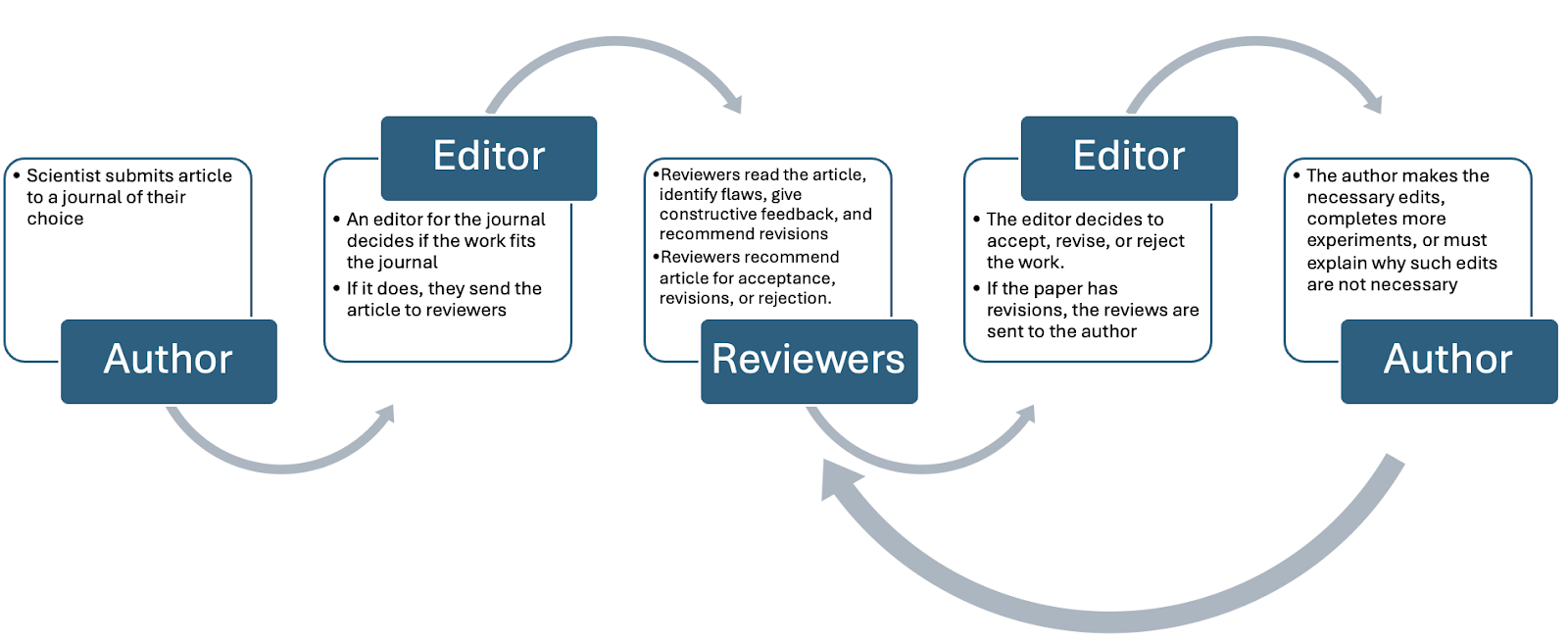

How does the peer review process work though? It begins with the scientist. They select a journal to submit their work to for publication. The scientist can report who might be a good reviewer for the article, and who should not review the article (for personal or professional reasons). An editor for the journal will make the decision to send the article to review based on fit for the journal. They select a panel of reviewers and ask if they will review the work. Reviewers receive manuscripts and raw data from the authors and evaluate the work for quality, accuracy, and novelty. They check that experiments are designed properly and that methods are described clearly enough for others to replicate. Reviewers suggest changes, ask questions, recommend additional experiments, and can even reject the paper. This promotes transparency in science as it fosters open debate, creating a forum for experts to challenge and improve each other’s work, generating a culture of accountability in research. Papers often go through multiple rounds of review and revision, ensuring the final product is polished and reliable. This openness shows the public that science is a collaborative and self-correcting process. The public knows that published research isn’t just one person’s opinion—it’s been vetted by experts. Ultimately, the journal decides whether to accept, revise, or reject the paper based on the reviews. It is uncommon for papers to be accepted without requiring revisions.

Image Source: Author created image. Flow chart describing the peer review process.

The peer review process has many benefits. It improves the overall quality of research by providing authors constructive feedback, suggestions, and ensures that conclusions follow logically from the evidence. Reviewers can identify inaccuracies, problems in experimental methods, and any gaps that need to be filled. This process can also foster new connections between authors and reviewers. While reviewers may initially be anonymous, they may choose to disclose that they reviewed the article. This can potentially lead to collaborations between laboratories and further research.

Even with all of the benefits, the peer review process is not perfect. While scientists try to prevent it, there is still some reviewer bias. Sometimes personal opinions can influence decisions. Additionally, some articles still contain inaccuracies. While peer review catches many issues, it is not perfect, and some rejected articles are still published in other journals. Reviewers are often unpaid, meaning they have to juggle this work with their own research and responsibilities. It can also be a slow process.

Sometimes this process fails. One of the most famous and long-lived examples of this is from a 1998 study by Andrew Wakefield that falsely linked the MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine to autism. Published in The Lancet in 1998, Wakefield’s study claimed to find a link between the MMR vaccine and autism in 12 children. It sparked widespread fear of vaccines, leading to a decline in vaccination rates and outbreaks of preventable diseases like measles. What went wrong? There was a very small sample size that made it near impossible to draw meaningful conclusions, Wakefield failed to follow proper scientific protocols, and he did not disclose that he had received funding from lawyers preparing a lawsuit against vaccine manufacturers, creating a massive bias in his work. Larger studies later found no link between the MMR vaccine and autism. Investigations revealed that Wakefield altered data to fit his hypothesis. After these issues were uncovered, The Lancet fully retracted the paper in 2010, stating that its claims were “false.” Wakefield also lost his medical license for unethical behavior and misconduct. Although the original study was peer-reviewed, its flaws went unnoticed until further scrutiny after publication. Science relies on repeated studies to confirm findings, which Wakefield’s study failed to achieve. Despite the retraction, vaccine hesitancy fueled by this paper continues to affect public health. This example serves as a stark reminder of how flawed science can have far-reaching consequences and why rigorous peer review and ethical standards are crucial in maintaining trust in science.

You may be asking how can you trust science when articles such as the above are published and not retracted until over 10 years later? It’s a valid question, and skepticism is a healthy part of understanding how science works. While cases like Andrew Wakefield’s flawed study highlight imperfections in the peer review process, science as a whole has mechanisms to self-correct and improve. One study, even if peer-reviewed, isn’t enough to establish a scientific truth. Other researchers test and replicate findings to confirm or challenge the results. And once published, research is subjected to further scrutiny by the broader scientific community. Flaws in Wakefield’s study were exposed by follow-up investigations and larger studies. Peer review is a critical step, but it’s not perfect. Reviewers are human and can miss errors, especially in cases of deliberate misconduct like Wakefield’s. However, it’s just the first filter. Science relies on a combination of transparency, replication, and accountability to validate findings. Scientists also learn from mistakes: cases like Wakefield’s have led to stronger ethical standards, better disclosure requirements, and more rigorous review processes. Many journals now encourage data sharing, open peer review, and pre-registration of studies to reduce bias and fraud.

The strength of science lies in its collective, ongoing pursuit of knowledge, not the perfection of individual studies. While errors and misconduct can occur, the scientific community is equipped to detect and correct these over time. Trust in science doesn’t mean believing it’s perfect; it means understanding that it’s a rigorous, self-correcting process dedicated to uncovering the truth.

Image Source. Person in a crowd holding a sign saying “In Peer Review We Trust”.