by Clark Hickman

A “biblical flood.” That’s how some officials in Buncombe County of western NC described the impacts of Hurricane Helene after the storm dumped upwards of two feet of water on that portion of the state and caused record flooding in the region. The devastation that ensued is hard to put into words. Entire communities were destroyed (Fig 1) as the influx of water raced down the usually picturesque mountains and into saturated streams, creeks, and rivers. Hundreds of lives were lost in the region, and, a month after the storm, local ERs are still struggling to deal with the fallout of that week. Rivers such as the French Broad, Swannanoa, and Catawba all reached record levels (Fig 2); as they overflowed their banks they began picking up trees, roads, bridges, cars, businesses, and homes and taking them along for a very turbulent ride. This debris would be deposited downstream, leaving a “war-zone,” checkered with basins swept clean by the water followed by regions where all of that debris was deposited in a jumbled mess. Four weeks after the last of the rains have passed, some residents in the region still do not have clean water or electricity in their homes, if they still have homes at all.

Fig 1: Satellite imagery of Chimney Rock taken before and after (Oct 7, 2024) the floodwaters from Hurricane Helene swept through the town. Images created from NOAA satellite data.

Fig 2: Height of French Broad River in Asheville during Hurricane Helene. Peaking at a record 24.6 ft, the flooding that ensured surpassed even that of the Great Flood of 1916. Image created by author with data and template from USGS.

Southern Appalachia and the Blue Ridge Mountains are no stranger to flooding. Despite its label as a “climate haven” due to the region’s (more) moderate temperatures, distance from the coast, and reduced fire danger, locals are well-aware that living in mountains prone to rain comes with some risk, mostly in the guise of landslides, tree damage, and flooding. Rain from the remnants of hurricanes has hit the region multiple times in the past. Yet the decimation from this storm is on a completely different level from previous events. The damage was exacerbated by a stalled cold front in the region that kept some of the early rain bands from the hurricane stationary while the storm was still gathering energy and moisture in the Gulf of Mexico. By the time the full force of the storm arrived, the area had already seen close to a foot of rain, leaving the soil saturated. As more rain fell and the winds picked up, mountainsides turned to mud and, having lost their foundation holding them to the steep slopes, massive trees toppled and joined the debris washed down the mountain. Even days later, the saturated soil continued to cause trees, roads, and buildings to collapse.

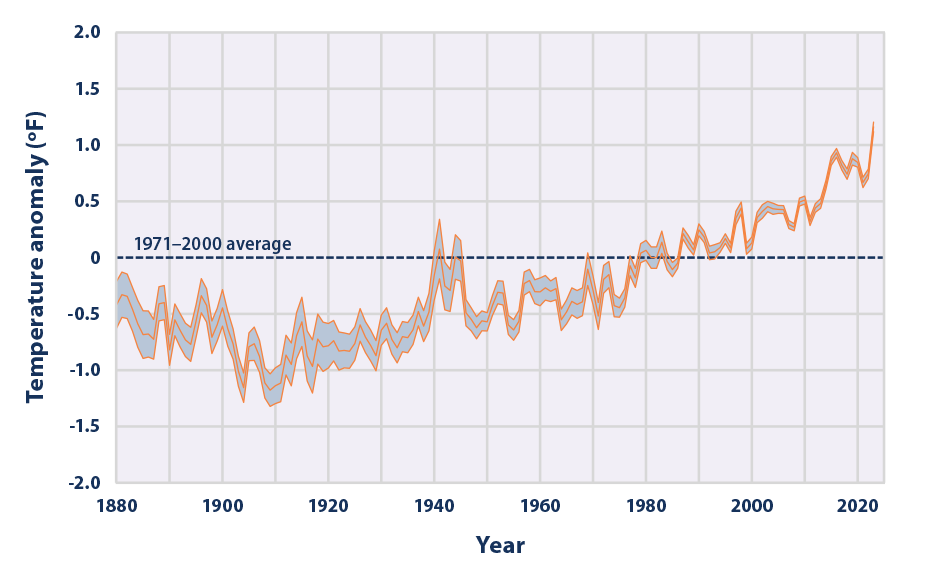

Reports in the weeks that followed the cyclone attributed up to a 50% increase in precipitation due to climate change. To understand why, it’s helpful to take a step back and understand the basics of hurricane formation. Hurricanes – the Atlantic’s version of tropical cyclones – form over the warm waters of the ocean in the summertime months. When a low pressure disturbance in the area creates an increase in wind, that wind evaporates the warm water vapor from the ocean. As the warm air rises, it condenses to form clouds and new, cooler air rushes in to fill the space left by the rising air. This cycle continues to build larger and larger storms until upper atmosphere wind shear breaks it up or the cyclone runs out of fuel by leaving the warm waters. Unfortunately, the amount of fuel available for these monsters has increased as the planet’s warmed. Water is an extremely effective heat sink – it has a higher specific heat capacity than air so it can absorb more energy without as big a change in temperature – so much of the energy of the warming atmosphere has been deposited in our oceans (Fig 3). These warmer waters do not mean that more hurricanes will form, but it does make it more likely that those that do have more energy and emerge stronger than they would have previously. The past decades have also seen a sharp increase in “rapid intensification” of hurricanes due to the warming waters (Fig 4). Not only does warm water increase the overall energy in the storm, but as warmer air expands, it can hold more moisture (consider how much more humid the summer months can be than the winter), meaning hurricanes can dump more rainfall and do so even further inland.

Fig 3: Ocean temperature has increased drastically over the past several decades. Warmer oceans provide more energy for tropical cyclones and can leave them much stronger than they had been previously. Source: EPA.

As North Carolinians, we can hope that we won’t see another storm of this magnitude during our lifetimes, but we are playing a dangerous game with our climate. As recent years have shown, we should be prepared for more hurricanes like Helene (And Beryl. And Milton.) and design our society with climate resilience in mind because Mother Nature will have her say, one way or another. (If this article has you down, don’t forget we are making progress on climate change, especially in areas of renewable energy. This article highlights some of the encouraging news that came out of COP28.)