by Daniela Danilova

Tangy, crunchy, juicy, refreshing – all in all, delicious. From the dainty cornichon to the jumbo dill, everyone’s got their pickle of choice. Pickling has been both a tasty and practical trick for ages, transforming foods far beyond the classical cucumber. It’s time to dive into the inner workings of this timeless technique.

Flipping through your mental food history reserves, where does the pickle fall within this extensive timeline? If your answer is somewhere amongst the era of the hotdog or sliced bread, you’d be sorely mistaken. Pickles can be traced back to the ancient Mesopotamians, who, over four thousand years earlier, preserved cucumbers in very salty water known as brine. Since then, pickled foods have attracted a number of A-list clientele who, altogether, had an impressive variety of reasons behind their admiration. For Egypt’s Queen Cleopatra, a promise of unmatched beauty kept her hooked on a pickle-infused diet. For her other half, Roman general Julius Caesar, pickles were a staple in his soldiers’ diets as a strength-promoting supplement. Fast forward a few thousand years and the pickle continued to spot historical records, this time courtesy of Christopher Columbus. The famed explorer was to keep his crew supplied with the salty snack to prevent them from developing scurvy, a nasty disease borne from Vitamin C deficiency.

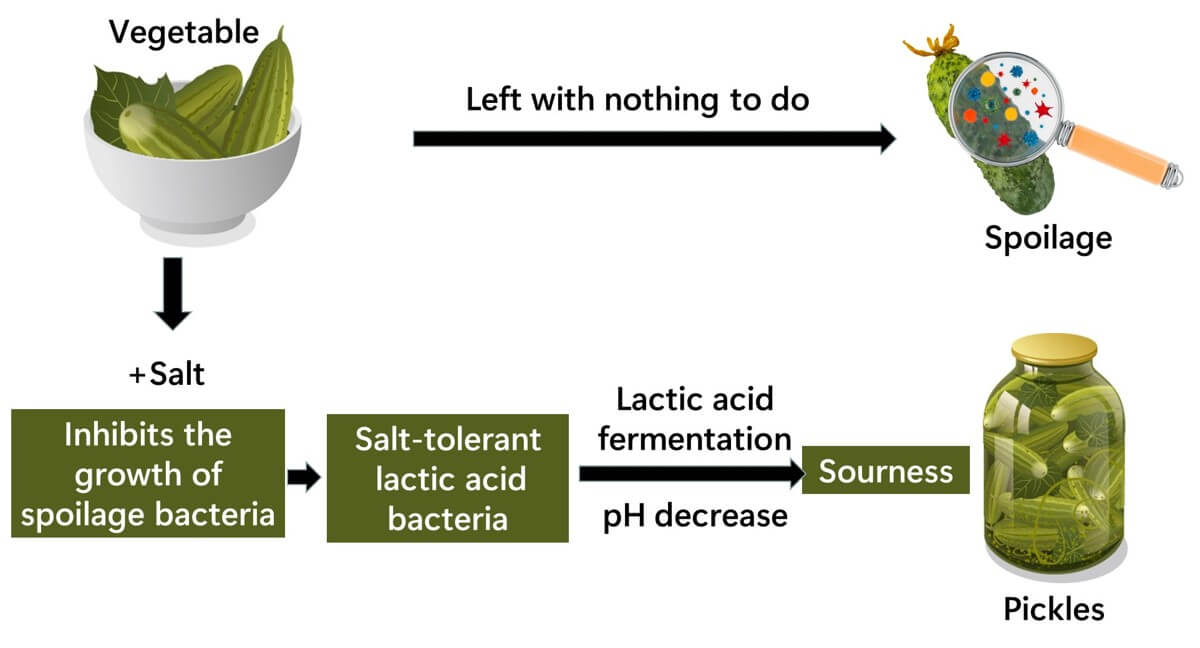

When it comes to pickling, there are two main routes to achieve the signature taste. In chemical pickling, foods are soaked in concentrated liquids like brine, vinegar, alcohol, or vegetable oil. This process is an attractive preservation method as it not only results in the familiar sour taste, but also kills any present microorganisms. On the flip side, fermentation pickling involves storing the food in conditions that promote the growth of special lactic acid bacteria. Sealed away from the outside world in airtight jars, the bacteria thrive as they gobble up sugars within the food of choice. In a specific process known as lactic acid fermentation, the bacteria spit out lactic acid, which mixes with the rest of the pickling pool and is absorbed by the jar’s contents. This is where pickled items get their characteristic acidic flavor profile. Furthermore, picklers have invested a great deal of time into concocting unique and memorable recipes for their personal creations – perfecting everything from timing to spice blend and even storage temperatures.

Special bacteria are able to produce lactic acid, the source of the sourness. Image Source: foodmicrobe-basic.com (link)

If there’s one version everyone’s heard of, it’s the dill pickle. As an herb, dill hails from the Arabian Peninsula, but the dill pickle itself came to prominence in New York. In the 19th and 20th centuries, swaths of Eastern European immigrants arrived to America, bringing with them recipes for kosher dill pickles. By the 1930s, Pickle Alley was a blossoming enclave in the Lower Manhattan area. Competition was so intense that several vendors became embroiled in a spat over the right to the namesake business of Russian immigrant and prolific pickle master Izzy Guss, erupting in a legal battle that persisted into the early 2000s.

The art of pickling is far from limited. Numerous cultures have applied it to everything from cabbage, olives, and garlic, to far less suspecting items like watermelon rinds and blueberries. Despite its robust history, even this process is not immune to “innovation”, as evidenced by the existence of products such as the controversial kool aid pickle. Whether it be out of parody or pure curiosity, let’s hope pickling continues to find new ways to capture our imaginations and our taste buds.

Delectable or disturbing? You decide. Image Source