by Anna Goddard

Do you ever hear your parents talking about how bad Brussels sprouts used to taste? They remember them as a bitter, smelly, and overall unpleasant vegetable. And yet, today we see Brussels sprouts on dinner menus all over the place! Are your parents just being over-dramatic? Are we simply better at preparing them (Hello-o-o, bacon!)?

The answer is no, Brussels sprouts really do taste differently than they did 30 years ago. Brussels sprouts were first cultivated in the namesake Brussels, Belgium in the 16th century. In the 1990s, Dutch scientist Hans van Doorn identified the chemicals that made Brussels sprouts taste so bitter: glucosinolates. Glucosinolates are natural components of many pungent plants, and Brussels sprouts contain two of them, sinigrin and progoitrin, which explains where they got their smell. However, these bitter-tasting chemicals are an important component of the plant’s defense. Leaf-eating insects and animals don’t like the acrid taste, either. Glucosinolates are also responsible for many of the health benefits associated with Brussels sprouts and other plants in their family, as the products of glucosinolate degradation have been found to possess antioxidant and anti-cancer properties.

Fortunately, some of these glucosinolate culprits can be removed or have their chemical structure altered to maintain health benefits while lessening the harsh taste. Hans van Doorn and the chemical company Novartis were able to accomplish this with Brussels sprouts through cross-breeding and selection. Along with other companies, they began to search for older, less bitter varieties of the plant’s seeds. Through selective cross-breeding of the older sorts with the more modern ones, scientists created newer, much sweeter options. The first of these novel varieties, called Maximus, was introduced to the market in 1994.

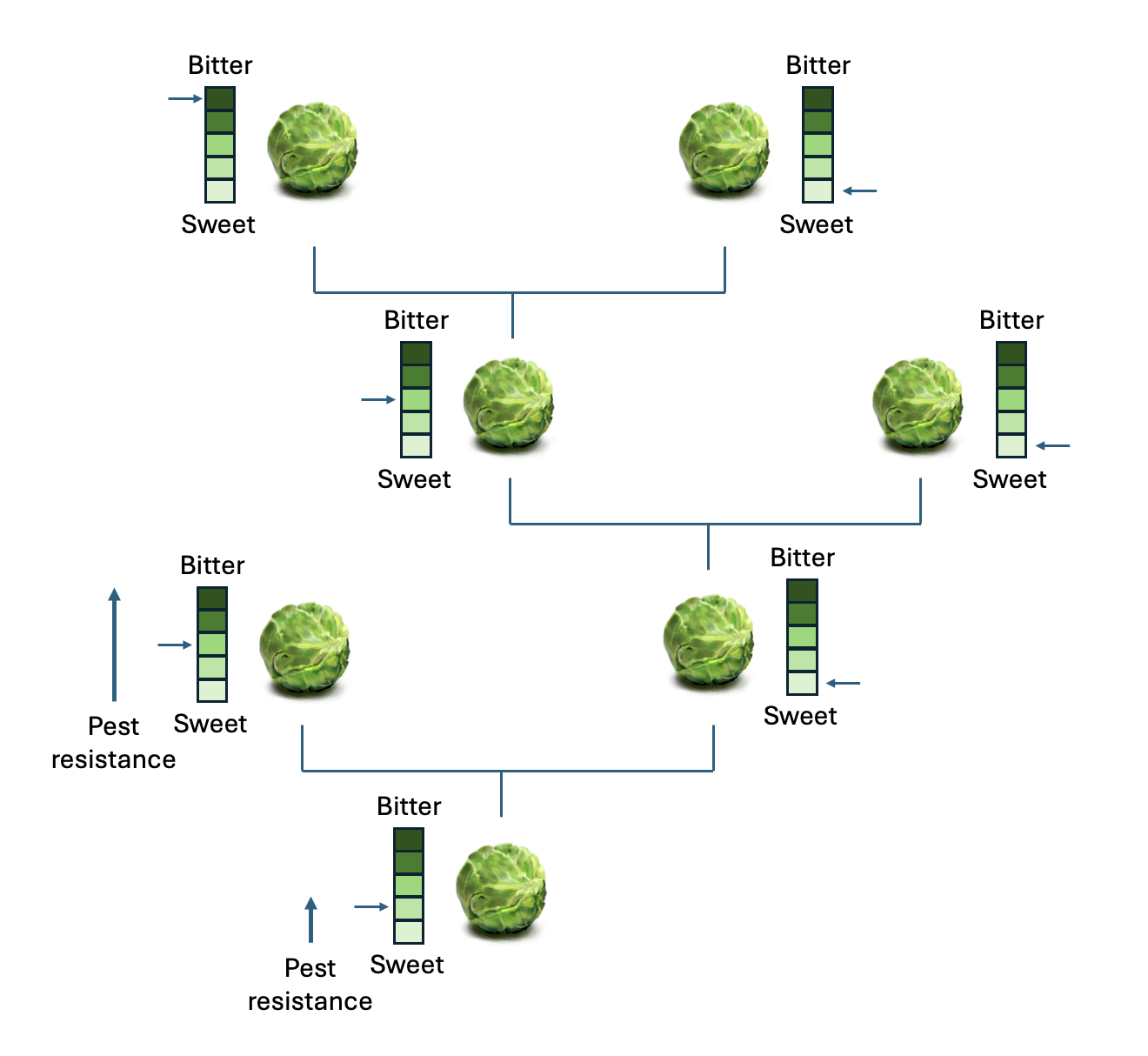

Selective cross-breeding of Brussels sprouts. Image created by author.

Selective cross-breeding is very different from genetic engineering creations like genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Selective cross-breeding is a method of artificial selection in which humans preferentially choose individuals with certain genetic profiles, called genotypes, and physical properties, called phenotypes, to breed together and, hopefully, achieve ideal collections of characteristics in the offspring. Genetic engineering, on the other hand, involves introducing specific genes to an organism that are not already present in that organism.

Syngenta, the company that sprouted from the agriculture portion of Novartis, is still working on perfecting Brussels sprouts, and newer varieties were introduced in 2012. While taste is an important factor to improve on, their other focuses include pest resistance and increased shelf life, both of which are also being enhanced through selective breeding. Like many major innovations, these changes didn’t appear overnight. Even now, developing new sprouts takes six to eight years.

Still think Brussels sprouts taste bitter? That’s most likely due to your genetics. Genetic differences between individuals make us more or less sensitive to bitter flavors depending on the presence and quantity of your taste receptors for bitter chemicals. But even then, Brussels sprouts won’t taste nearly as bitter as they used to!