by Maya Bluitt

For a lot of us, external stimuli – the feeling of a t-shirt hanging on you, the smell of coffee in the next room, the sound of people having a conversation outside – can fall into the background. Sometimes, these subtleties in the environment are more prominent, and can even cause one to feel overwhelmed. It turns out that for 15-20% of people, increased awareness of stimuli is a daily occurrence.

External stimuli is perceived by our many senses – vision, hearing, touch, taste, and smell; but also temperature, pressure, and more – and processed by the brain to make sense of our surroundings (see Figure 1). Sensory processing sensitivity (SPS) is a personality trait that causes heightened sensitivity to what’s happening in the environment. Generally, those with SPS process physical, emotional, and social information more deeply than others. People with SPS may show increased awareness of sensory input, like bright lights and loud noises. They could also have a stronger emotional response to external and/or social stimuli.

Figure 1. Painting entitled “The Five Senses” by Sebastian Stoskopff, 1633. Image source.

Because external stimuli can feel overpowering, individuals with SPS can often feel the need to remove themselves from sensory-rich situations (like crowded, busy environments). On the other hand, high sensitivity to external stimuli can also promote one’s ability to benefit from favorable environments. Moreover, those with SPS are often more empathetic than those without SPS.

Because SPS is a complex personality trait, figuring out the hundreds to thousands of genes that underlie it is a distant dream of scientists. However, researchers can conduct studies on twins to determine if SPS has any genetic component. Such studies have shown that SPS may be moderately heritable, meaning it may be a trait that is passed down to children.

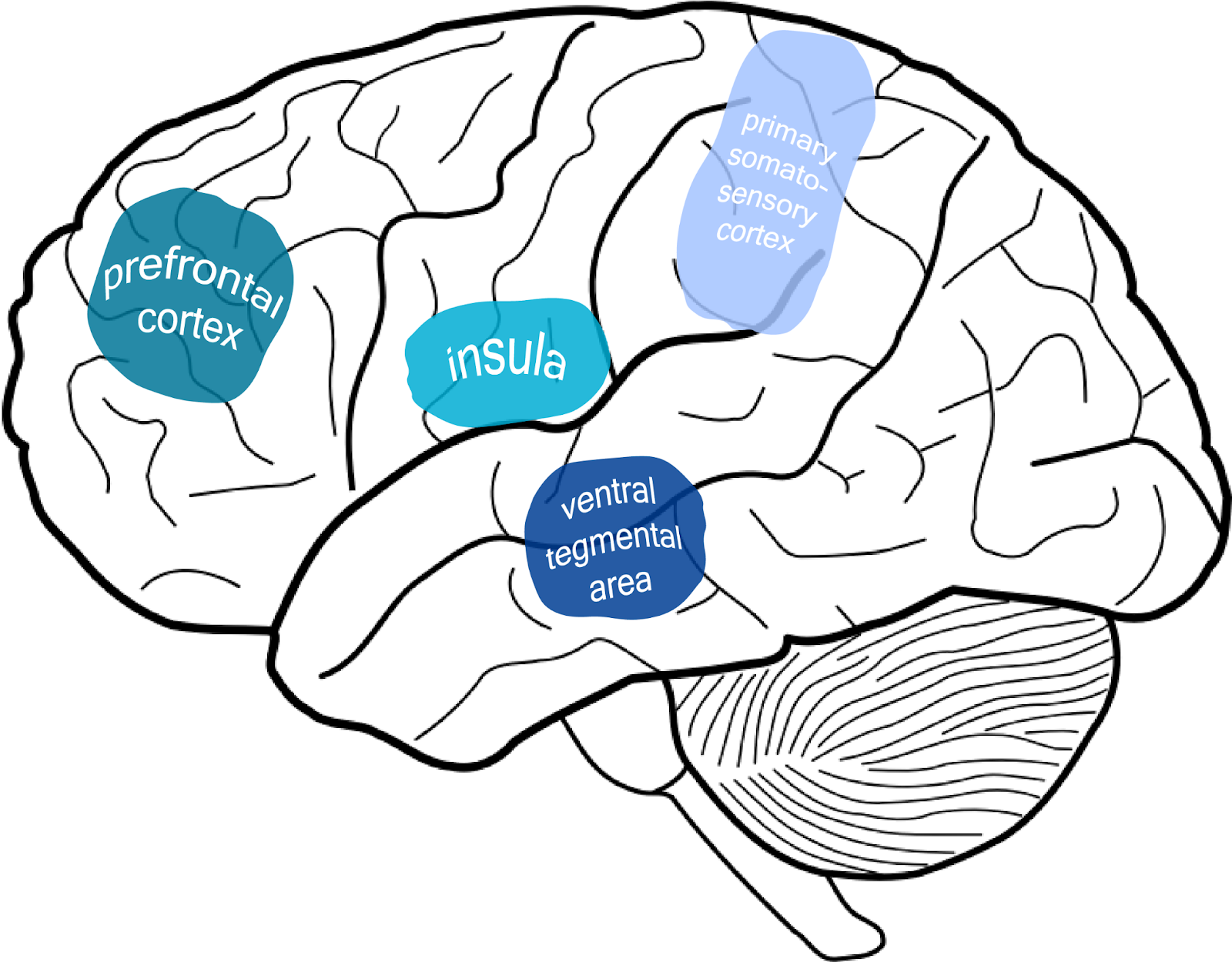

Neuroscientists have also found particular regions in the brain that may mediate SPS. While many brain regions are involved in SPS (see Figure 2), some examples include the insula, a region associated with subjective feelings, and the ventral tegmental area (VTA), a region involved in reward processing. Brain areas like the insula may be more responsive to touch, whereas the VTA may show more activation in response to social stimuli.

Figure 2. An fMRI study by Acevedo et al. 2014 identified the insula, the primary somatosensory cortex, the VTA, and parts of the prefrontal cortex as brain regions with major roles in SPS. Image adapted by author.

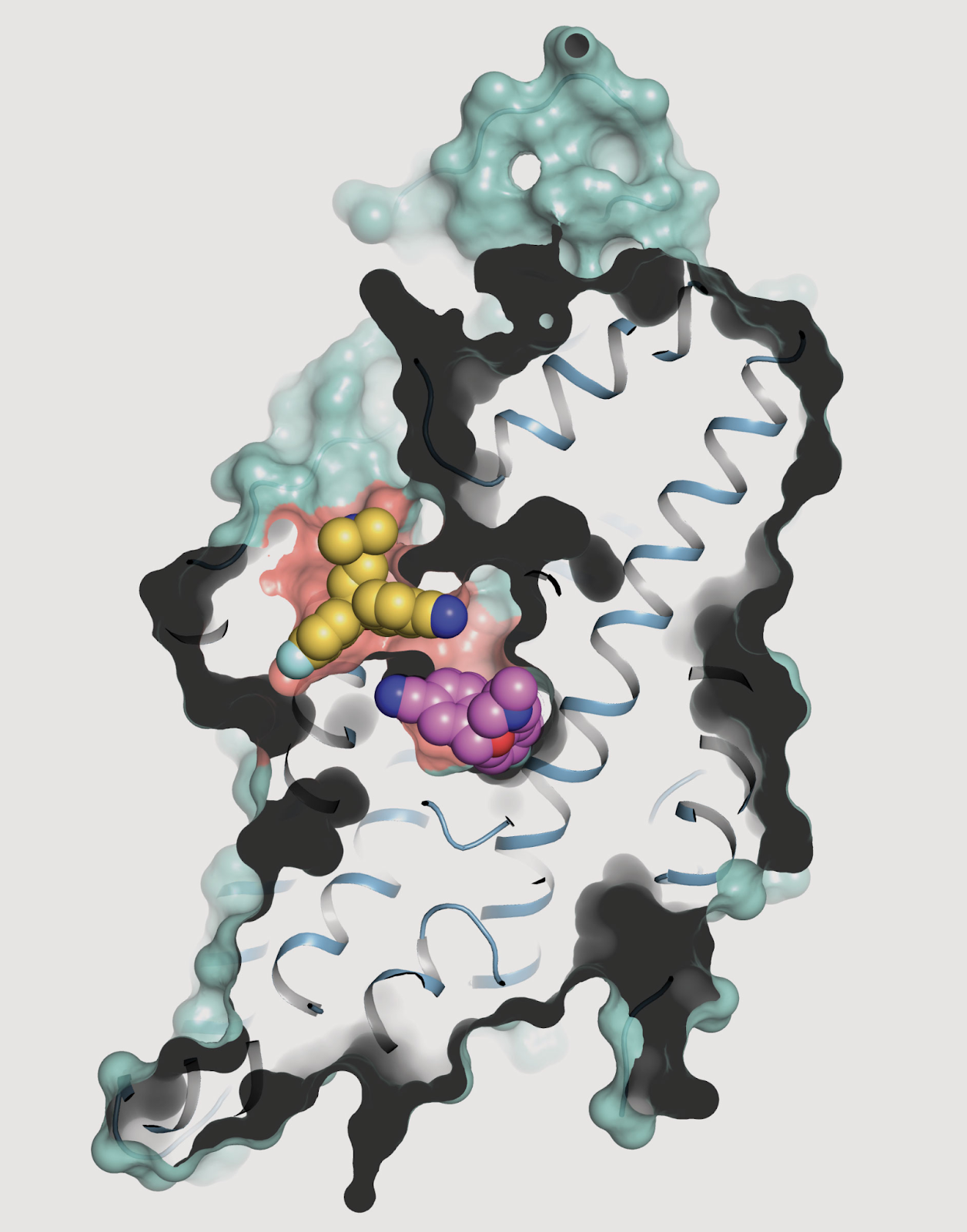

On a smaller scale, researchers are also beginning to get an idea of what type of neurotransmitters may be involved in SPS. One particularly notable neurotransmitter is serotonin, which plays roles in mood regulation, arousal, stress, and more. A small study in humans found a link between SPS and a gene that encodes a type of serotonin transporter (see Figure 3), which brings serotonin back into neurons so they can fire it again. Moreover, rodents that have their serotonin transporters removed show behavioral traits that are similar to those of people with SPS. Together, these studies suggest that unbalanced levels of serotonin in the brain may lead to enhanced attention to external stimuli.

Figure 3. A 3D rendering of the structure of a serotonin transporter. The yellow and purple dots represent the areas where serotonin binds. Image source.

While many people can feel overwhelmed from external stimuli from time to time, SPS may give a name to those who struggle with frequent overstimulation. While it’s a relatively common trait within the human population, there’s still much more research to be done to uncover the neural underpinnings of SPS. Despite this, there are strategies to cope with sensory overload, such as deep breathing and meditation.