by Maya Bluitt

Just about anybody would agree that your teenage years are both the best and worst times of your life. There’s a reason so many people share this sentiment: the brain undergoes a transformative shift during adolescence that positions teenagers to feel the good – and the bad – more deeply.

The brain is nearly fully grown, in terms of volume, by age 6. Accordingly, scientists assumed for many years that major changes to brain structure and function only occurred in utero (before birth) and during the first several years of life. It turns out that the brain undergoes a massive reorganization during adolescence, the period spanning from puberty to mid 20s.

Changes in structure

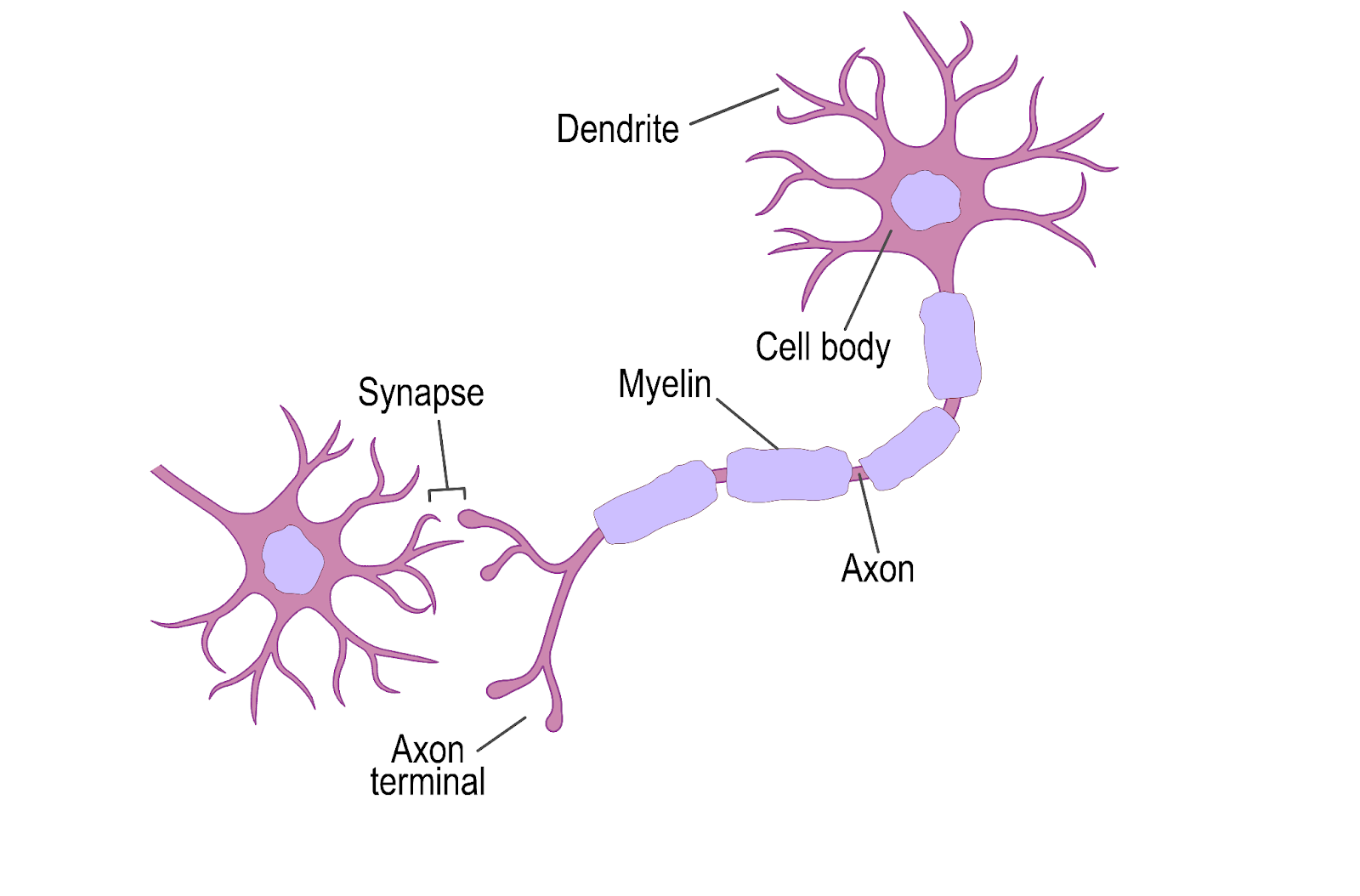

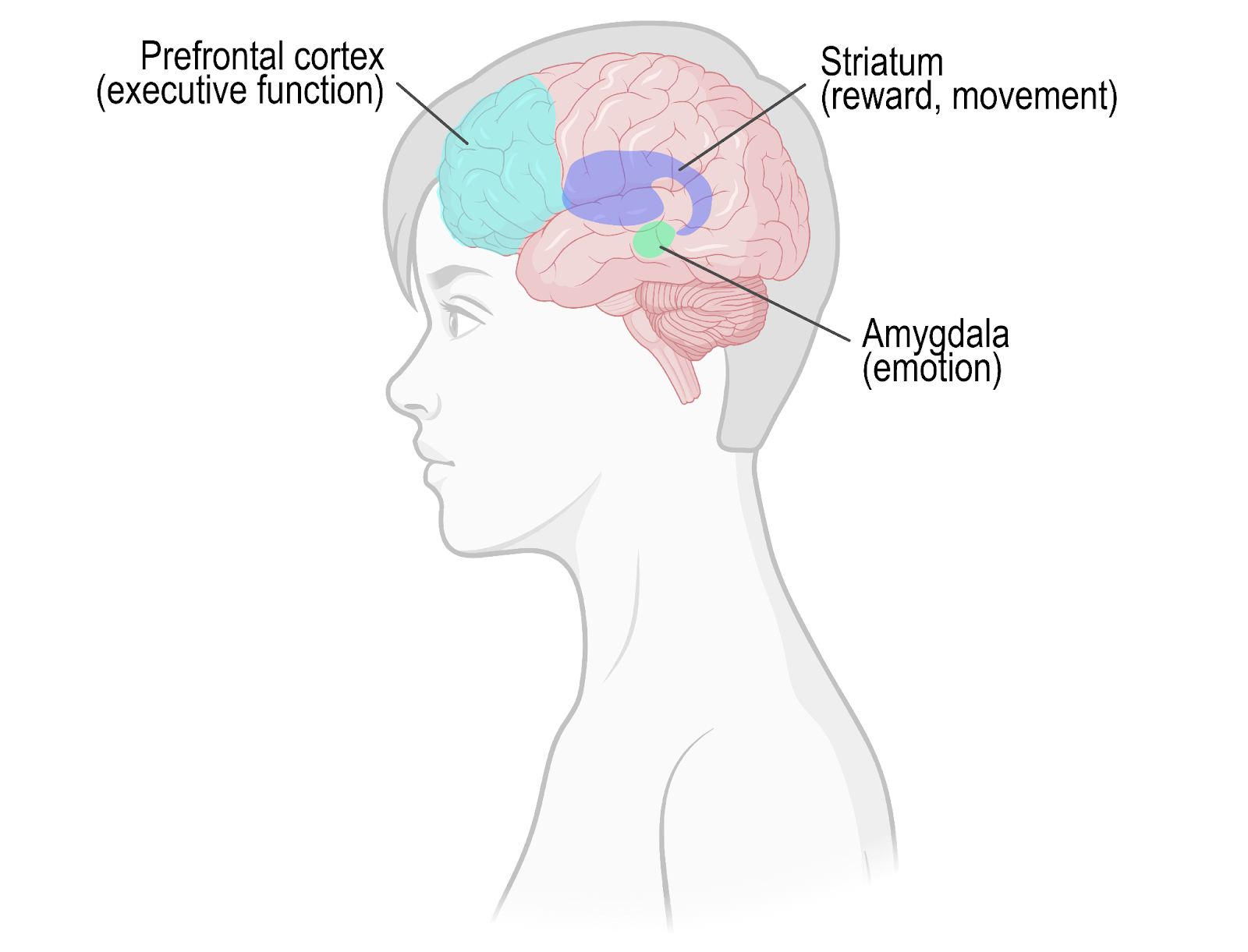

One of the most profound and well-replicated findings about brain development during adolescence is that gray matter and white matter bidirectionally change. There are decreases in gray matter (Figure 1), which is located on the outermost parts of the brain and holds the cell bodies of most neurons (brain cells; Figures 1 and 2). These changes in gray matter are due to a process called synaptic pruning, where connections between neurons that are no longer needed are removed. Synaptic pruning begins in the back of the brain, in regions that are associated with sensory and motor skills. The prefrontal cortex (Figure 3), which plays a major role in ‘executive functions’ like decision-making, planning, and impulse control, is last to go through this process and thus last to fully develop.

Figure 1. Gray matter and white matter in the brain. Image adapted by author in Adobe Illustrator.

At the same time that gray matter decreases, the amount of white matter (Figure 1) increases. White matter is on the inner part of the brain and primarily contains axons (Figures 1 and 2), which extend out from the cell bodies of neurons and allow them to communicate with one another. The volume of white matter increases because axons continuously receive the addition of myelin (Figure 2), which insulates them to speed up communication between neurons.

Figure 2. Diagram of a neuron. Figure made by author in BioRender and Adobe Illustrator.

Changes in function

The widespread structural changes the adolescent brain experiences contribute to and coincide with changes in function. One brain region that functional differences most notably occur in is the prefrontal cortex. Synaptic pruning in this region improves the efficiency of some ‘higher-order’ brain processes, such as information processing, self-awareness, and social skills.

While the development of the prefrontal cortex isn’t complete until the mid 20s, the limbic system, which regulates emotion and reward, peaks much earlier in adolescence. Studies have shown that compared to children and adults, adolescents have increased activity in a region of the limbic system called the striatum (Figure 3) in response to rewards. This increased activity makes adolescents more sensitive to rewards, explaining why teenagers are more likely to seek out new experiences and take risks. Another limbic region that shows increased activity is the amygdala (Figure 3), which is responsible for interpreting threats and generating strong emotions. This may underlie teenagers’ tendency to feel moody and impulsive.

Figure 3. Graphic of major brain regions undergoing change during adolescence. Figure made by author in BioRender and Adobe Illustrator.

These major findings regarding prefrontal and limbic systems have been applied to create a theoretical model of adolescence. It describes adolescence as a period of imbalance caused by relatively early development of limbic regions and relatively delayed maturation of the prefrontal cortex. The result of this imbalance is that thoughts, feelings, and actions during adolescence are likely to be driven more by emotion and reward, and less by rational decision-making.

This reliance on limbic systems may make teens more prone to making rash decisions and acting on emotion. But it’s also what drives teenagers to seek new friends, show increased prosocial behavior, and develop a strong sense of self. For teens themselves, these insights should encourage them to challenge themselves and to embrace all that adolescence offers.