by Hazel Milla

Stress is a normal part of our daily lives that can help us succeed or lead to emotional troubles and burnout. Whether you’re preparing for an upcoming exam or exposed to extreme temperatures, your body undergoes changes that are meant to help you adapt to the situation. When you face something stressful (also called a stressor), two responses ensue: a fast response, also known as your fight-or-flight response, and a slow response. These responses are coordinated by the brain as well as various organs and glands within the body.

The fast response:

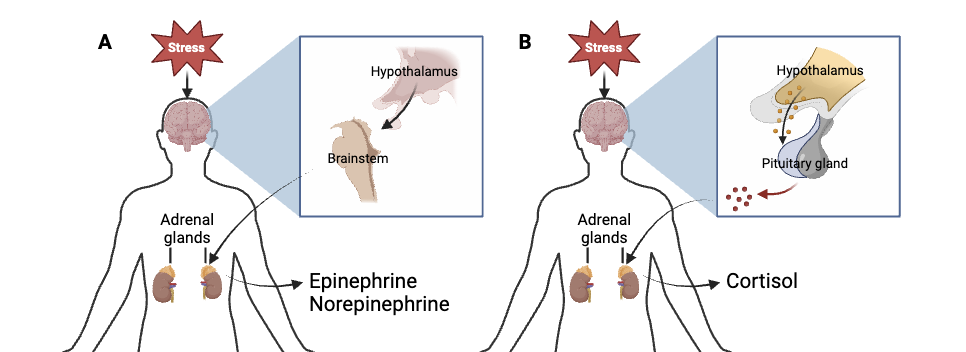

This short-term stress response occurs within seconds of exposure to a stressor. For your fast response to kick in, the part of your brain called the hypothalamus signals to the brainstem, which induces the small glands located above your kidneys, called adrenal glands, to produce norepinephrine and epinephrine. These hormones travel to different parts of the body to effect changes such as faster heart rate, increased blood pressure, and heightened focus, to name a few.

The slow response:

The long-term stress response starts within minutes to hours of stress exposure. During this time, the hypothalamus signals to the pituitary glands, causing them to release a hormone that prompts the adrenal glands to produce cortisol. Cortisol is a hormone which is often referred to as the body’s stress hormone. This hormone increases the amount of glucose (a molecule used as a source of energy) circulating in the blood. It also signals to the body to stop storing energy and instead use it up to address the stressful situation. This allows the body to continue responding to the stressor as needed.

Figure 1: A) The fast stress response. B) The slow stress response. Image created by author using BioRender.

Why do these changes occur?

Humans often face potential sources of harm that may disrupt the body’s functioning. Because of this, we have evolved stress responses that help maintain homeostasis (the body’s normal, healthy state). When faced with potential danger, a person needs to be alert so they can respond quickly to the threat. This is achieved thanks to epinephrine and norepinephrine signaling. These substances also increase blood pressure and respiration, helping your body transport more oxygen to your muscles, which is necessary if you need to fight or flee when in danger. Cortisol is useful in that it allows your body to mobilize its primary energy source (glucose) to your muscles, better facilitating movement. Epinephrine, norepinephrine, and cortisol also prompt immune cells to assemble in preparation for potential infection or injury that may result from the stressor.

Does stress only happen in bad situations?

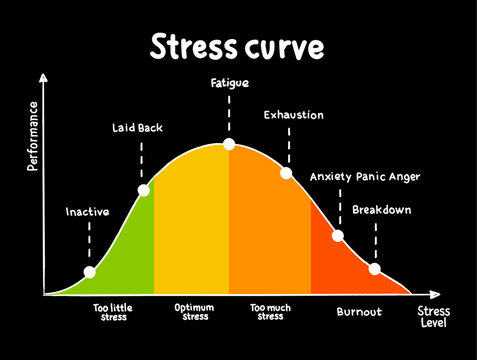

In your daily life, you may notice that your body’s stress response doesn’t just occur in bad situations. You may experience a stress response when you’re playing a sport or riding a rollercoaster, activities that many people find enjoyable. This is because the stress response not only makes us more alert to possible danger, but helps us focus on tasks that are beneficial to our survival. In the case of humans who are hunting and gathering for sustenance, the body’s stress response can make someone perk up to potential food sources and prepare them for an ensuing chase to find prey. Whether a stressor causes a positive experience of stress (also called eustress) or a negative one (distress) often depends on whether or not the individual experiencing the stressor feels like they can address or cope with the stressful situation without feeling overwhelmed.

Figure 2. An optimum level of stress (eustress) helps people perform tasks successfully. Too much stress (distress) can lead to unpleasant emotional states and burnout. Image source: Dizain, Adobe Stock