by Maya Bluitt

It’s a scenario all too familiar: Imagine you’re writing a paper for a class when your phone lights up with an Instagram notification. You scroll through the app for a bit, then decide to give yourself a more official break to watch some videos on TikTok. You know you should get back to your paper, but have a hard time shifting your focus away from social media.

Why is social media so good at keeping our attention, even when we try to avoid it? To answer this question, let’s first consider human social behavior from an evolutionary perspective. The ability of humans to communicate and connect has been crucial to the survival of our species across thousands of years. Accordingly, humans have evolved to seek out social connection just as we seek other things critical to our survival, like food and sex.

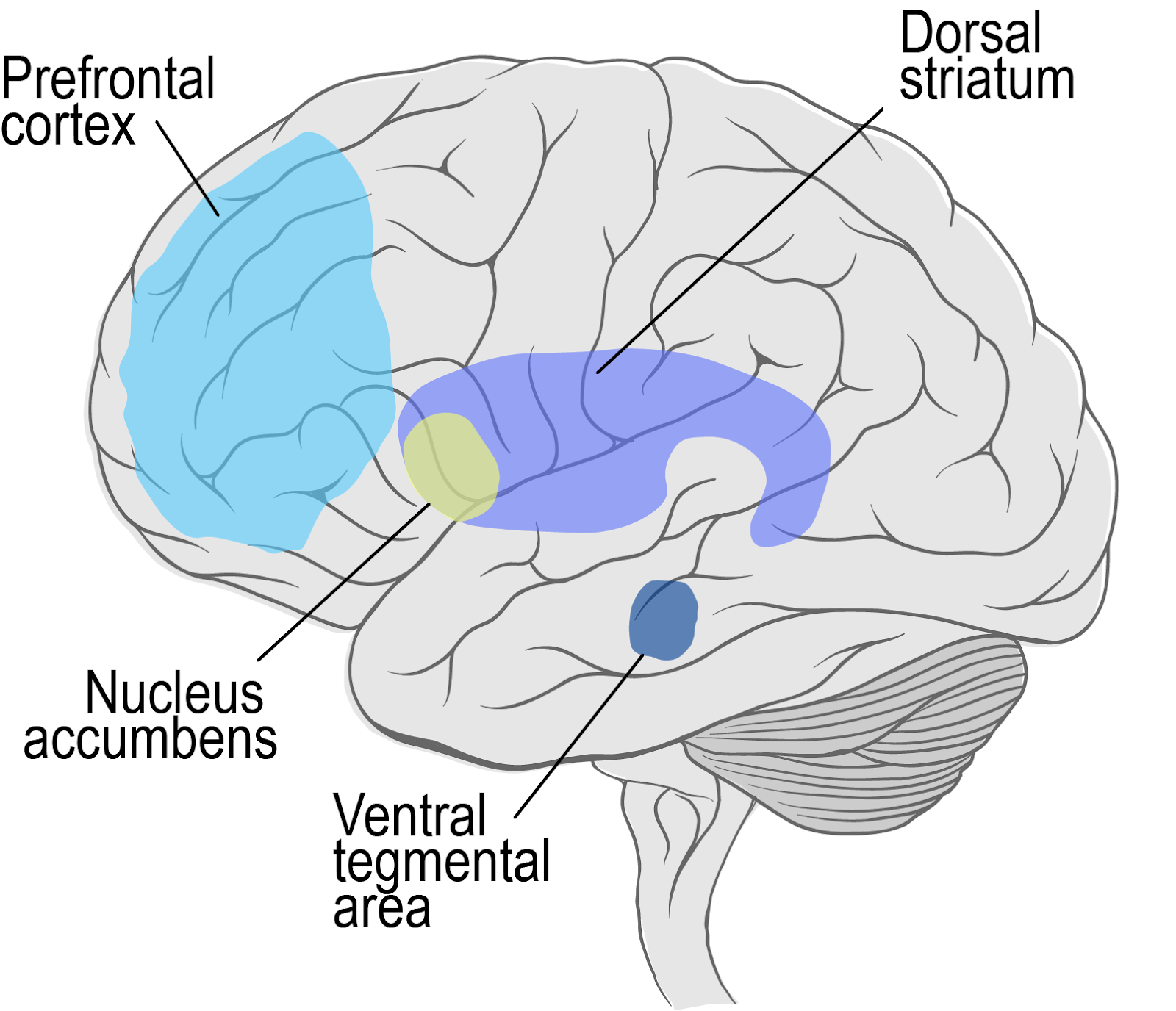

In fact, social behaviors activate the same network of brain regions that are activated when pursuing other rewards like food and sex. This ‘reward pathway’ includes the prefrontal cortex (PFC), ventral tegmental area (VTA), and nucleus accumbens (NAc; also referred to as the ventral striatum), among other brain regions. These brain regions take part in various aspects of social behaviors. For example, the PFC and NAc are activated in response to receiving positive social feedback about one’s personality traits. Sharing information about oneself activates the NAc and VTA.

Image adapted by author.

Unsurprisingly, reward pathways are also activated for social behaviors that take place online. For example, giving and receiving likes on social media platforms like Instagram activate the NAc and VTA.

While activation of reward pathways can be beneficial to survival (such as in the case of food and sex), social media presents one potential problem – there’s an overload of social content, providing excessive opportunities to engage these brain regions. When we continue to activate reward pathways with social media, we may be priming our brains to continue responding to it. For instance, one study showed that the more time a person spends on social media, the greater the activation of their NAc in response to a gain in reputation.

As scientists continue to explore the effects of social media on the brain, they are particularly focused on its effects during adolescence, the time period between puberty through mid 20s. The developing brains of adolescents are particularly sensitive to peer feedback and social interaction, leading scientists to hypothesize that social media may affect teens differently than adults.

A recent study from scientists at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill suggests social media may affect brain development during this time period. They show that adolescents who check social media frequently (referred to as ‘habitual’ behavior) show increases in activity in the PFC and NAc as they continue to habitually use social media over several years. Those who didn’t check social media often showed decreases in activity over time. Given these brain regions are involved in reward (as discussed above), this increased activity in habitual users may affect their sensitivity to social rewards and feedback from their peers in general.

It’s important to note that all of these studies look at correlations, and scientists are currently unable to determine if social media is causing changes in the brain. Moreover, many different types of experiences – not just social media use – have the ability to affect brain function. While brain changes associated with social media use may further promote habitual use, they may also help us adapt to a society which increasingly relies on technology.