by Daniela Danilova

It happens all the time. You go to the store looking for a simple evening meal; yet, minutes later, you find yourself walking away from the register with handfuls of extra snacks. Perhaps the guilt is already setting in: “I promised myself I wouldn’t spend that much money!” Don’t be quick to take all the blame. People are constantly swindled into buying things they don’t actually need by clever advertising and pricing strategies designed to convince them that they do. Welcome to the intricate world of marketing.

Ideally, the important financial decisions we make should be driven by cold, hard data and statistics. Although “gut” feelings can give us ideas on which paths will lead to the largest rewards, analyzing data is the only way we’ll know for certain whether our decisions are paying off. This fact is well-known in the business space, where a survey of over one thousand senior executives carried out by PwC, a professional services giant, showed that data-driven businesses were three times more likely to report large improvements in their decision making when it comes to developing new partnerships or investing in new markets. And it makes sense: Knowing that your choices are backed by numbers, you will become more confident about making similar decisions in the future.

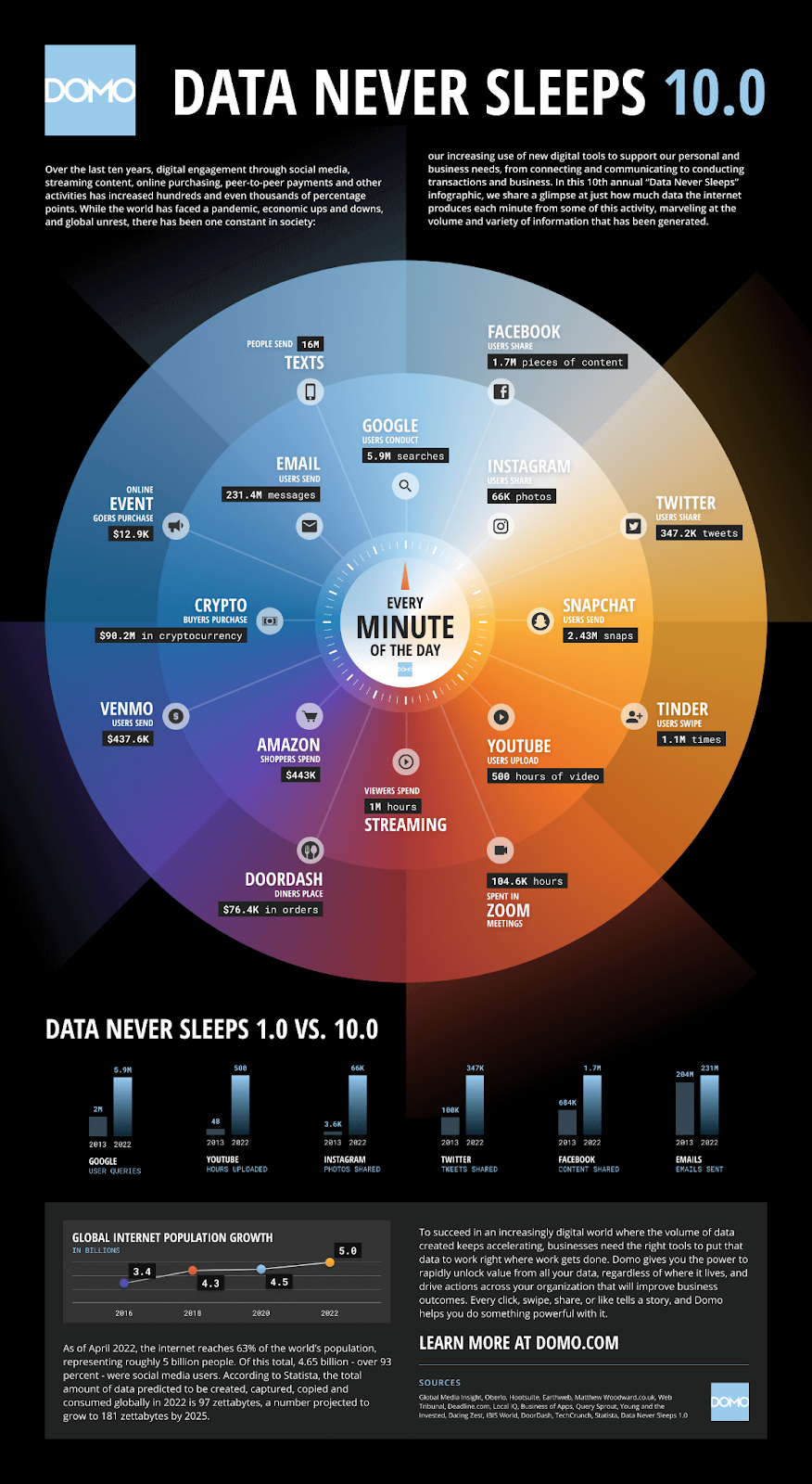

Fig.1: A huge amount of data is shared every minute of every day (Source)

However, individual humans are more impulsive than carefully-managed corporations, often trusting their intuition instead of the facts, and companies take advantage of these quirks in our decision making. Again, there are some pros to having good intuition. As of 2017, humans generated an average of around 2.5 quintillion bytes of data per day (that’s 25 followed by 17 zeros!). There is just too much information to rummage through in search of a clean answer, so you have to rely instead on your instinct to parse out what matters. The reality is that nobody has time to devote to making perfect picks when it comes to mundane activities like grocery shopping, so these experiences are transformed into races to see which company can grab the consumer’s attention first. The red-yellow color combination, for example, is known to instill a sense of hunger and hurry… McDonald’s or Burger King, anyone? Although we know there are healthier and cheaper options out there, those logos are designed to be far too enticing to pass up. Brands want to make it seem like purchasing their product is the answer to your problems, which makes emotionally-driven campaigns so vital. Using this strategy, Coca-Cola has successfully linked their name to the holiday season and all of the joyous feelings it brings. Who are you to turn down Santa Claus’s advice to sit down and enjoy a refreshing Coke with family on Christmas?

Fig. 2: A jolly Santa Claus enjoying his glass of Coca-Cola (Source)

Interestingly, even seeing certain numbers can change our minds. A ubiquitous example is the 99-cent ending used in many prices. This deliberate decision rests on the existence of “fluent” numbers. These are considered to be familiar, even friendly, because we spend many years practicing counting with them as children, and because we continue to encounter them as adults. Numbers such as 16, 18, and 20 are fluent, whereas numbers like 13 and 19 are not because they are prime and not often stumbled upon. There is also the concept of highly-numerate consumers, or those more comfortable with numbers, who tend to round 99-cent endings up because they focus on the entire price; and less-numerate consumers, or those less comfortable with numbers, who will round those prices down because they pay more attention to the digits to the left of the decimal point. Knowing this, sellers can set price points depending on which categories their buyers fall into. For instance, if sellers know that people are willing to pay around $17 for an item, they could take advantage of more-numerate buyers by setting the price at $17.99, which will unconsciously be rounded up to a fluent $18.

Little tricks like these are ingrained in our markets; and, considering their success, there is no prospect of these tactics dying out anytime soon. It would be easy to tell someone to be more diligent with how they spend their money, but the pace of everyday life makes it impossible to ponder over every financial investment. Nevertheless, next time you find your arm reaching for a random item on the store shelf, ask yourself, “Who is convincing me to buy that?”