by Imani Madison

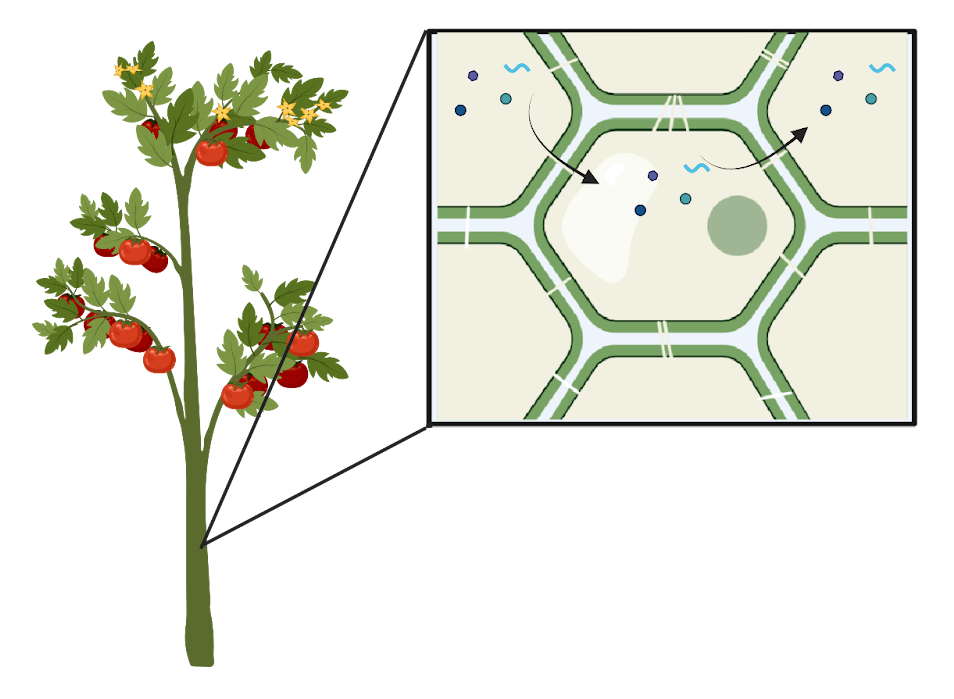

Plants are unable to physically move from their location to find nutrients or escape harm, so they have to respond quickly to changes in their environments. When their roots need sugar, roots must tell leaves to boost sugar production and transport sugars down to the roots. When leaves need more iron, leaves must tell roots to look for iron in the soil and move it up to the leaves. If a virus infects a leaf, the infected cells must close themselves off from the rest of the plant to prevent pathogenesis. Plant cells also regularly talk to each other to make sure they all mature properly during the plant’s life cycle. Thus, there are channels between plant cells that control the flow of these messages from one cell to the next called plasmodesmata (PD) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PD channels between plant cells allow nutrients and signals to be moved throughout the plant as depicted in the diagram of a cross-section of a stem. (Created by author with BioRender)

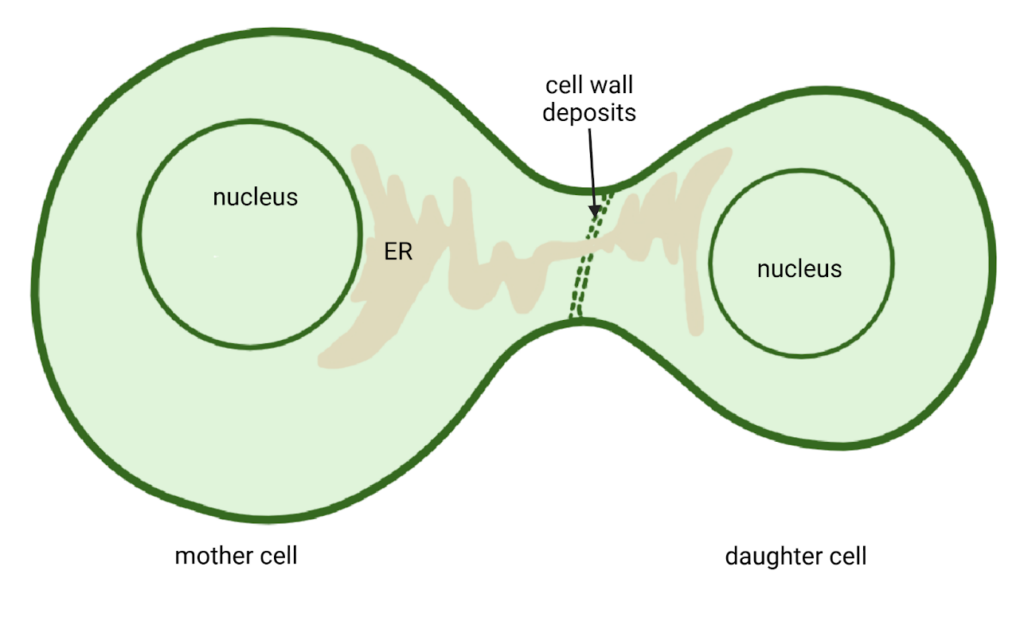

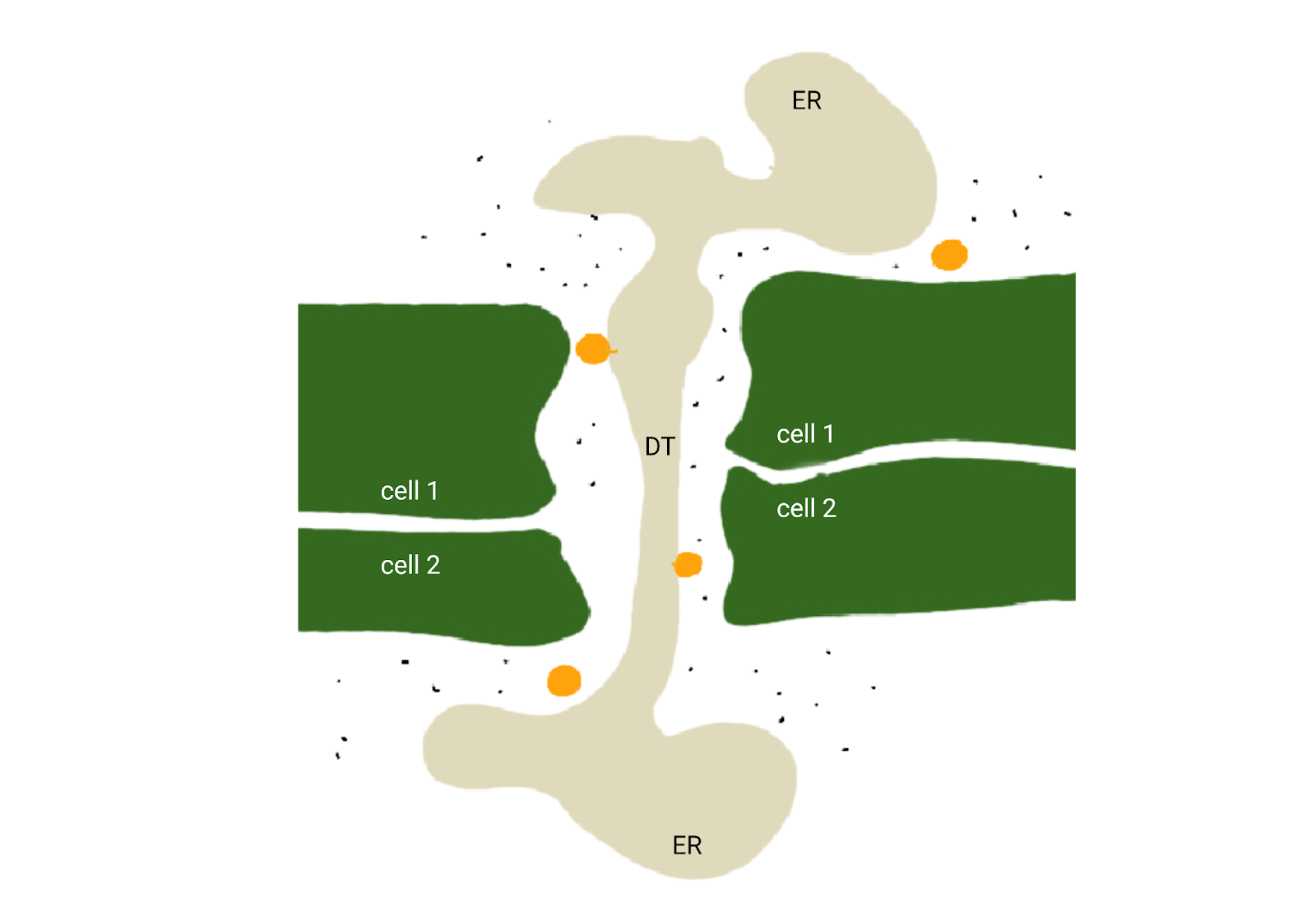

PD usually are formed during cell division. During cytokinesis, segments of the new cell wall are deposited between the dividing mother and daughter cells (Figure 2). As the segments are deposited, strands of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) are trapped between them. PD channels are then formed around the strands, creating connections between the mother and daughter cells. The strands of the ER are converted into structures called desmotubules (DT). The DT is like a track that pulls proteins through the channel (Figure 3). PD are also made by other (unknown) methods and can have more complex shapes such as multi-channel or funnel-shaped structures.

Figure 2. During cytokinesis, strands of the ER become trapped in cell wall deposits between dividing cells, which will eventually become PD. (Created by author with BioRender)

Figure 3. Cross-section diagram of an open PD channel with small molecules (black) and proteins (orange) moving from one cell to another. Two proteins (orange) are shown bound to the DT as they travel through the PD. (Created by author with BioRender and Procreate)

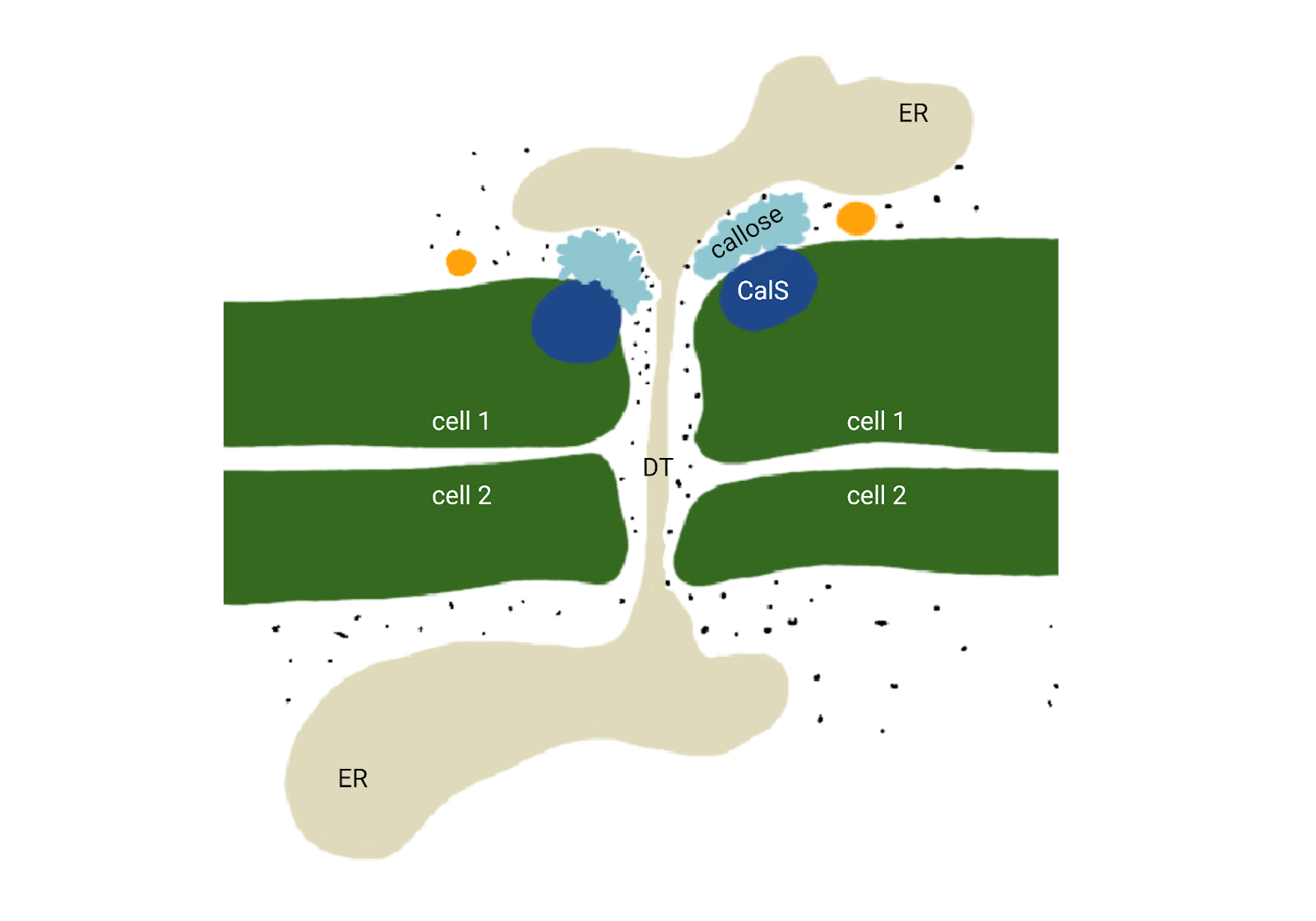

Cells open and close PD to control what moves between them. Callose Synthase (CalS) proteins are located at the entrance of the PD. When needed, cells tell CalS proteins to produce a plug, made of callose, to block the PD entrance (Figure 4). During viral infections, CalS proteins in infected cells plug their plasmodesmata with callose to prevent viruses from moving from cell to cell. Cells can also control how much callose is made. For example, CalS proteins make just enough callose to block larger-sized molecules (like proteins) from entering the channel while allowing free diffusion of small molecules (like sugars) (Figure 4). Cells can also control which specific proteins or messenger RNA (mRNA) can enter PD by active mechanisms that are still being discovered. Without cell-to-cell communication, it would be difficult for the plants we heavily rely on for food, clothing, and oxygen to efficiently support themselves.

Figure 4. Cross-section diagram of a closed PD channel with small (black) molecules moving from one cell to another and proteins (orange) blocked from moving by callose plugs (light blue). CalS proteins (dark blue) are shown at the entrance of the PD (Created by author with BioRender and Procreate)