by Chelsea Smith

You walk into a friend’s house, sit down, and start to feel a slight itch in your nose. Then, you start sneezing. Before you know it, your eyes are watering and you are itchy all over. That’s when it hits you: they have a cat.

In Western countries, about 10-30% of people are allergic to cats. Although cat dander is not harmful, the immune system sometimes mistakenly identifies it as dangerous, leading to an allergic response. The immune system exists to defend our bodies against microorganisms that can cause us harm, such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi. To do this, it generates many types of antibodies, each of which bind to a specific allergen, priming it for destruction. This function is essential for our survival, yet allergies to things that are not dangerous, including cat dander, can develop.

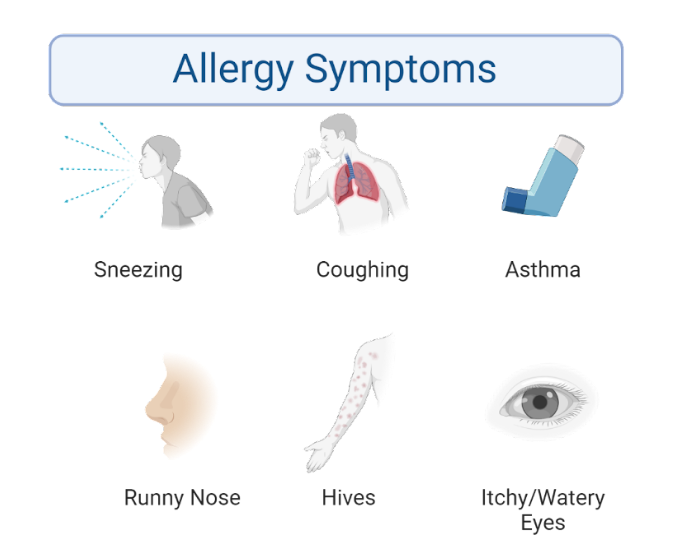

Image 1: An allergic reaction to cats can include symptoms such as sneezing, coughing, asthma attacks, runny nose, hives, and itchy or watery eyes. Image generated by author in BioRender.

When the immune system is activated, the body unleashes an allergic reaction with symptoms that can range from a mild runny nose and watery eyes to extremes such as trouble breathing or even anaphylaxis, a life-threatening response that induces swelling of the throat and a sudden drop in blood pressure. These symptoms develop in response to inflammation in the nasal passages and lungs. Some people may also experience skin-related symptoms, such as red itchy bumps called hives.

Research has discovered that the majority of allergic reactions to cats is due to Fel d1, a protein specifically produced by this feline. Although a total of 10 cat allergens have been identified, Fel d1 is responsible for an overwhelming 95% of reactions to cats. Cats produce Fel d1 in their sebaceous glands, which are located on the skin, and in their saliva. While Fel d1 is thought to possibly have a role in protecting the skin, much of its function is still unknown.

Since the identification of Fel d1 as the main culprit causing allergies to cats, some researchers have begun looking into ways to reduce exposure to this allergen. One idea has been to introduce cat food that contains antibodies against Fel d1. The goal is to have the antibodies neutralize Fel d1 in their saliva as they ingest the food, and there has been some hopeful evidence. One study found that after 10 weeks on this diet, the amount of active Fel d1 on cats’ fur dropped by an average of 47%.

Image 2: In recent years, companies have begun to develop cat food containing antibodies against Fel d1. When fed to cats, the antibodies bind the Fel d1 protein in their saliva, neutralizing the protein and preventing allergic reactions against it. Image generated by author using BioRender.

Despite promising results, some cat owners worry what effect this food will have on their cats’ health. Fortunately, in 2019, a 6-month study found no effect on their wellbeing after eating kibble containing the Fel d1 antibody. Soon after, in 2020, Purina released their Pro Plan LiveClear Cat Food, aimed at helping cat owners deal with their allergies. With the possibility of widespread therapeutic benefits, it’s likely that in the near future, more studies will be done on this topic and more companies will jump on board in generating anti-allergy pet foods, all in the hope that we can one day snuggle with our cuddly friends without sneezing!