by Marco Gontijo

Fun Rating: 4/5

Difficulty Rating: 3/5

What is the general purpose? A macrophage invasion and survival assay helps scientists study in vitro how bacteria infect and survive inside macrophages in vivo, a type of immune cell that plays a key role in fighting infections. This technique allows researchers to understand which bacteria can evade the immune system and how our bodies respond.

Why do we use it? Some bacteria, like Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Salmonella, Listeria, and other pathogenic bacteria, can survive inside macrophages instead of being killed. This ability makes infections more challenging to treat. Scientists use this assay to:

- Test bacterial survival: See how long bacteria survive inside macrophages and which virulence factors are leveraged in this process.

- Study immune responses: Understand how macrophages try to kill bacteria.

- Test new treatments: See if antibiotics or immune-boosting drugs can help macrophages fight infections.

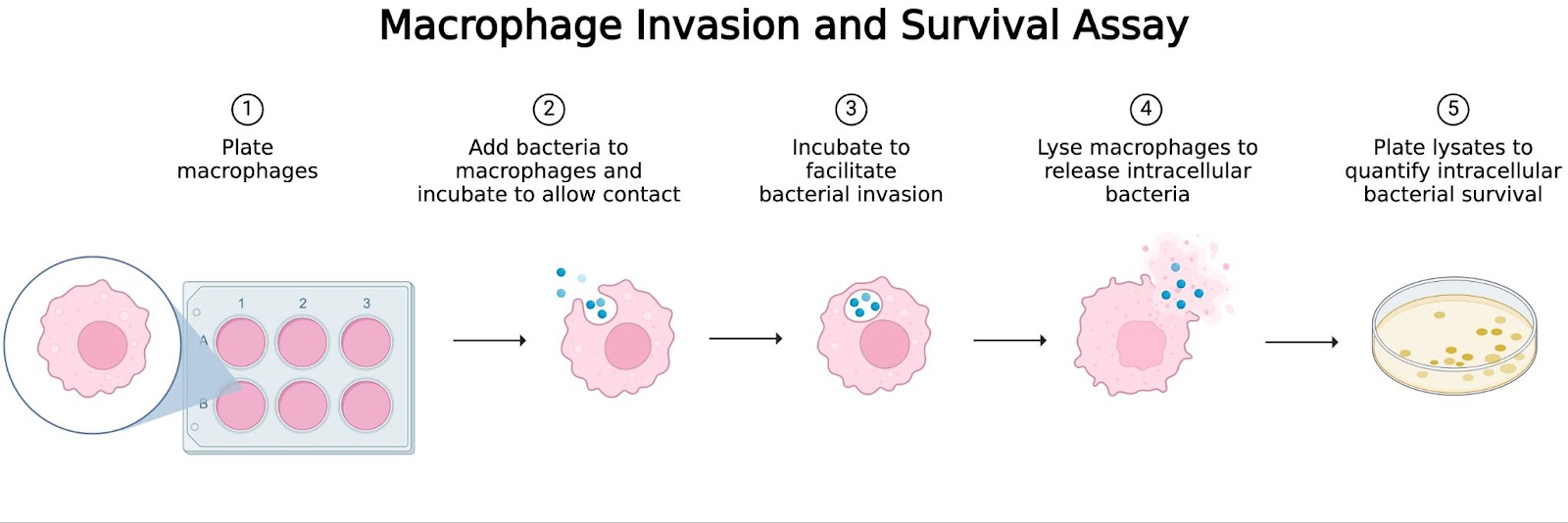

How does it work? The macrophage invasion and survival assay generally includes five primary steps (Figure 1). This technique was specifically tailored to study macrophages, but the same principles can be applied to other cell types that also help our bodies fight infection.

Figure 1. Invasion and Survival Assay at a Glance. Macrophage Invasion and Survival Assay Workflow. (1) Macrophages are plated and allowed to adhere to the plate. (2) Bacteria are added and incubated to allow time for contact. (3) Bacteria invade macrophages during incubation. (4) Macrophages burst open to release intracellular bacteria. (5) Lysates are plated to quantify bacterial survival by colony-forming unit (CFU) counting. Created by author in BioRender. Lab, S. (2025)

- Growing macrophages:

- Macrophages from an established cell line or primary cells (e.g., bone marrow-derived macrophages or human monocyte-derived macrophages) are seeded into multi-well plates or coverslips.

- The cells are incubated in media containing the necessary nutrients and growth factors to ensure they remain viable and functional for the experiment.

- Infecting the macrophages:

- The bacteria of interest are grown under optimal conditions until they reach the appropriate growth phase.

- The bacterial suspension is diluted to achieve the desired multiplicity of infection (MOI), representing the ratio of bacteria to macrophages.

- The bacteria are then added to the macrophages, and the plate is incubated for a set period (e.g., 1-2 hours) to allow bacterial invasion.

- Removing extracellular bacteria:

- After the infection, cells are washed multiple times with a buffer, such as phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), to remove non-adherent bacteria that did not invade macrophages.

- In some assays, an extracellular antibiotic treatment (e.g., gentamicin) is applied to kill any remaining bacteria, ensuring that only intracellular bacteria are measured.

- Measuring bacterial survival:

- To determine bacterial survival over time, macrophages are lysed at different time points post-infection (e.g., 4, 24, 48 hours) using a detergent or mechanical disruption method to release intracellular bacteria.

- The lysates are plated on agar plates and incubated to allow bacterial colony formation. colony-forming units (CFUs) are counted to quantify viable intracellular bacteria.

- Alternatively, bacterial survival can be assessed using fluorescence-based methods, luminescence assays, or qPCR to measure bacterial DNA or RNA levels.

- Comparing results: Some experiments include measuring macrophage responses to infection before lysis by assessing:

- Cytokine production (e.g., ELISA for TNF-α, IL-1β, or GM-CSF).

- Macrophage viability (e.g., live/dead staining or lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assays).

- Intracellular signaling pathways (e.g., Western blot for phosphorylation of immune-related proteins).

- Interpreting the Results:

- A high bacterial burden over time indicates that the bacteria can survive and replicate inside macrophages, suggesting immune evasion strategies.

- A rapid decrease in bacterial numbers suggests that macrophages effectively kill the bacteria through reactive oxygen/nitrogen species, autophagy, or other defense mechanisms.

- Comparing wild-type vs. mutant bacteria helps determine which bacterial genes are required for intracellular survival.